The growing role of federal and state money in combatting erosion and flooding at Chicago’s Lake Michigan shore offers an opportunity to mandate local governments make their beaches more open and equitable.

Chicago's Public Beaches

In shoreline metropolitan regions, summer means beach season. Public beaches in urban and suburban areas serve multiple purposes: vital shoreline ecosystems, recreational amenities, vital spaces for cooling down during hot summers—especially for households without air conditioning—and open spaces for the public.

But often, these spaces are open and public in name only. Unlike public parks, which tend to be free and accessible to all, public beaches in the United States often feature elaborate mechanisms to keep out non-residents, such as parking restrictions, security booths, and steep access fees that sharply restrict the public that beaches are meant to serve. In Chicago, this report's case study, the question of who has a right to public beaches has recurred periodically—particularly in moments of heightened racial conflict, such as the 1919 race riots and the backlash to the civil rights campaigns of the 1960s. Today, public access to public shoreline in the region is still determined by wildly different, often blatantly exclusionary rules, which depend on the location of the beach and the home address of the visitor. Many municipalities contest—even reject—the public's right to public shoreline.

As elsewhere, the Chicago region has seen these disparities, which tend to fall along racial lines, amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. As Mayor Lori Lightfoot closed the city’s normally free, open beaches for the summer because of concerns over viral spread, many suburban beaches remain open and accessible—but not to Chicagoans. Existing fees combined with new pandemic restrictions make non-residents' visits to some suburban beaches, already implausible, virtually impossible. At the same time that the city's infrastructure of air-conditioned public spaces and cooling centers—created after the 1995 heat wave killed more than 700 residents—has dwindled, the pandemic has exacerbated geographic, racial, and class disparities in beach access.

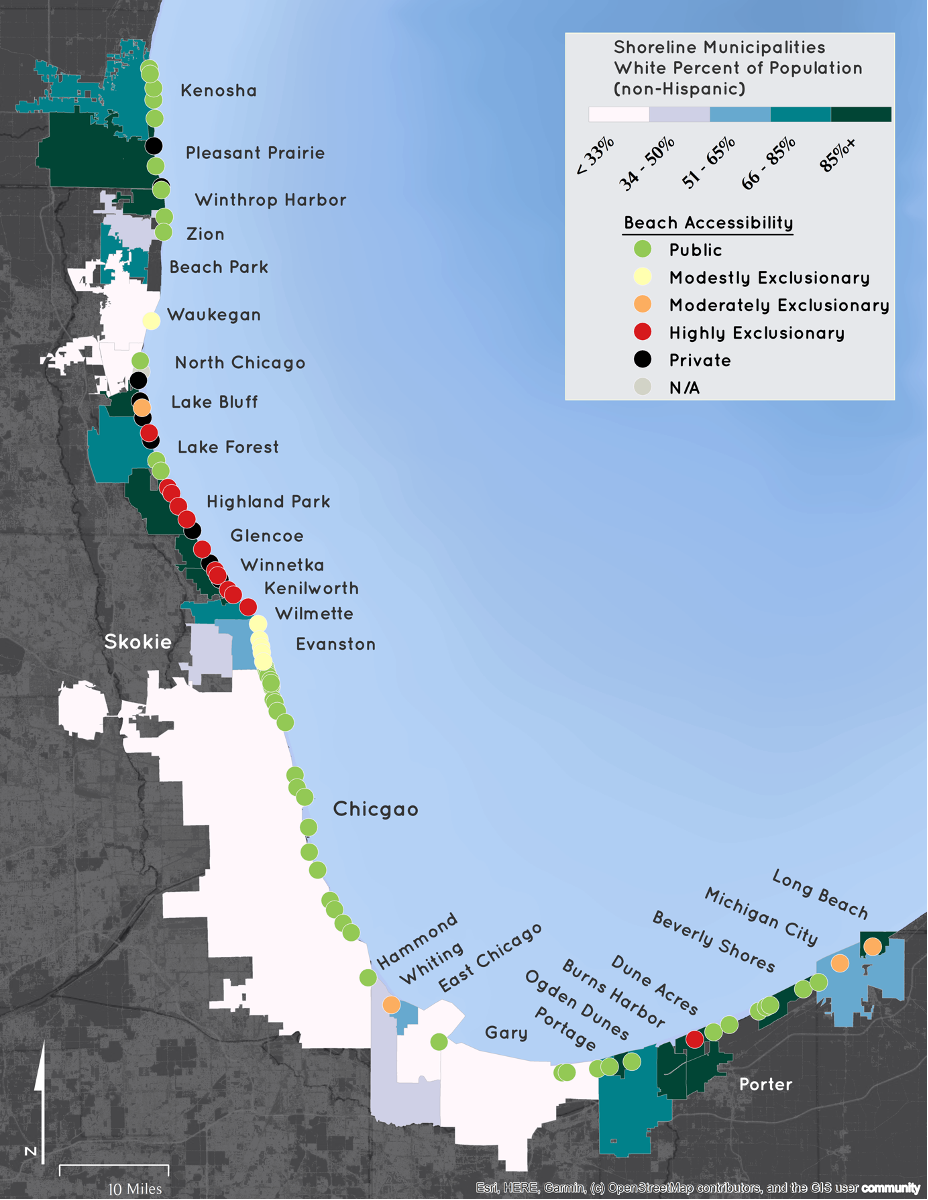

The result is a regional geography of racial and class inequality manifested in—and amplified by—access to the shoreline.

Executive Summary

Beach access restrictions are racist in their origins and racist in their effects.

From the start, municipal beach access restrictions either had explicit racist aims, or used "ostensibly race-neutral laws" to achieve racial and class exclusion.1 Beaches have also repeatedly served as sites in which white residents enforced racial segregation with force throughout the twentieth century.

The whitest, wealthiest municipalities have the most restrictive public beach access policies.

Chicago's whitest, wealthiest suburbs on the North Shore charge non-residents the most exorbitant fees. Racially diverse municipalities tend to be far less restrictive. North Chicago, Zion, Kenosha, East Chicago, and Gary—places with large nonwhite populations—each boast completely open beaches.

On public beaches with residency requirements, residential segregation leads to segregated beach access.

Municipalities which base public beach access on residency extend the failures of the housing market into access to public space. Housing segregation is most persistent in northern US metropolitan regions; in Chicago, practices such as redlining, "steering," zoning restrictions, and local activism against affordable housing have formed barriers which keep some suburbs' Black populations as low as .1% today.

In exurban areas, further from Chicago and other cities such as Gary, Indiana, these patterns begin to break down.

Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin, for example, is mainly white and middle-class, with no transit connections to Chicago. Its beaches are free and open.

Fragmented regional governance worsens the social and environmental inequalities of the shoreline.

The social disparities of shoreline management have environmental implications, as rapid fluctuations in Lake Michigan's water levels flood and erode the shoreline. Many municipalities have built seawalls, jetties, and other "armoring" structures to protect local beaches which exacerbate erosion and flooding elsewhere. Paired with exclusionary rules for nonresidents, these practices are likely to widen the economic and racial disparities in access to public beach land over time.

Overview of Recommendations

- Eliminate exclusionary beach access policies for nonresidents and use fair tactics to control crowding

- Tie federal and state erosion protection funding to open beach access

- Treat the shoreline as a regional system

- Adopt a racial equity lens for shoreline access

- Improve public transit access to public beaches

The Contested History of Public Beach Access

Municipalities can have good reasons to want to restrict access to beaches. Where demand for beach access greatly exceeds the supply of beach land—on a sunny holiday weekend, for example—a town may need tools to prevent crowding. In a pandemic, municipalities may want to preserve space for visitors to socially distance.

But the public beach access restrictions that govern Chicagoland and other metropolitan areas today have racist origins and effects. Well into the 20th century, northern municipalities in the US treated beaches as spaces for enforcing the kind of Jim Crow segregation commonly associated with the post-Reconstruction South. As historian Andrew Kahrl notes, municipal shoreline policies were directed towards racial and class exclusion, yet often used "ostensibly race-neutral laws" to achieve their aims.2

Sometimes, Black beachgoers were explicitly told they could not access a beach, or were confined to an undesirable area; other times, municipalities used elaborate means to enforce Jim Crow on the shoreline while obscuring their racist intentions. One New Jersey town, for example, required beachgoers to buy a ticket to access one of its four beaches—but when Black beachgoers bought tickets, they were given tickets to Beach 3 only. "Across America," Kahrl writes, "this was how many black children first encountered the color line: during summer and at the beach."3

After World War II, demand for beach land accelerated amid the demographic shifts of mass suburbanization and growing migration of Black Southerners to Northern cities. But the local and federal policies designed to meet this demand exacerbated racial and geographic inequality in beach access. Federal programs of the 1950s and 60s funded a massive expansion of recreational infrastructure that targeted disproportionately white suburban and rural areas. When cities did receive federal recreational funding, they tended to spend it in affluent white areas in an effort to forestall middle-class flight to the suburbs.4 City beaches tended to be informally segregated through the 1960s, and when racial boundaries were transgressed on the shoreline, whites repeatedly confronted African American visitors with violence.5

Throughout the 20th century, the racial injustice of beach access attracted attention from civil rights activists, especially in northern metropolitan regions. In the late 1930s, the NAACP successfully sued suburban Westchester County, New York, over its racially segregated beach policies. But rather than commit itself to integrating its public beaches, the county responded by selling most of them off to private clubs.6

Beaches again became a focus of civil rights activism in the 1960s and 70s. In Connecticut, Ned Coll led busloads of Black children from cities to the beaches of wealthy, white suburbs to highlight the relationship between the era's urban unrest and racial exclusion from the suburban shoreline. Suburban municipalities zealously resisted these campaigns. Confronted with the prospect of Coll bringing children to the local beach, for example, the town of Madison, Connecticut, tried to turn them away by requiring the children to undergo "physical examinations" before accessing the shoreline.7

Beach Access in Chicago's History

Until the late 19th century, public bathing in Chicago was banned, leaving beach access the domain of private beach clubs and outlying suburbs. North Shore towns such as Lake Bluff developed into beach towns, visited by wealthy Chicagoans who stayed in private resorts. Only in 1895 did the City opened its first public bathing beach in Lincoln Park, the result of a middle-class reform campaign to give poor and working-class residents a place to bathe for sanitary and health purposes.8

Though never segregated by law, Chicago's beaches were long segregated in practice. With the start of the Great Migration during World War I, Chicago's growing African American population confronted sharp limits in access to beaches, enforced by violent responses from whites. In 1912, for example, a Black child was attacked after attempting to bathe at the white 39th Street Beach, nearly causing a riot. Into the 1950s and 60s, African Americans visiting white beaches met conflict and violence upon entering—and apathy from park police.9

Beach access was also the catalyst of the bloodiest riot in Chicago's history. In 1919, the city's "red summer" began after Eugene Williams, a Black boy swimming in Lake Michigan, floated on a raft across the racial dividing line of 29th Street. Angry white beachgoers threw rocks at the boy, drowning him. The incident ignited a destructive weeklong riot that killed 38 Chicagoans, most of them Black. As historian Virginia Wolcott writes, the riots were as much a reflection of racial discrimination in access to recreation as those in housing and jobs.10

After World War II, so-called "recreation riots" in Chicago increased in frequency. In the 1950s and 60s, activists confronted beach segregation with "wade-ins," a northern shoreline counterpart to the sit-in demonstrations in the Jim Crow South. In 1960 and 1961, so-called "Freedom Waders," assisted by CORE and the NAACP, endured violent confrontations with local whites as they attempted to integrate Rainbow Beach on the South Side.11

As historian Arnold Hirsch writes, in postwar Chicago, "always… the worst violence occurred when the use of public parks and beaches was contested."12 As the postwar city experienced rapid racial change, challenges to the racial hierarchy provoked the most incendiary responses in the places where that hierarchy was most vulnerable—spaces purportedly open to all.

Beach Access in the Chicago Region Today

Today, methods of regulating beach access in metropolitan Chicago are subtler, but they continue to produce discriminatory outcomes and beaches largely segregated by class and race.

Local beach access regulations run the gamut in the Chicago region, from completely open and free to expensive and difficult for nonresidents to access. In analyzing the region's beaches, we categorized access according to the following levels of restriction:

| Open Access | Modestly Exclusionary | Moderately Exclusionary | Highly Exclusionary |

|---|---|---|---|

| No fees | Parking restrictions for nonresidents, but parking available | Access fees for nonresidents of $50-100 for season pass; $15 or less per day | High fees for nonresidents (more than $15/person) |

| Accessible via public transporation | Parking fees generally | Parking fees of $15-25 per day | Parking restrictions for nonresidents with poor transit access |

| Available parking | Annual pass under $50 | Separate entrances for nonresidents | |

| Cost for nonresidents only modestly higher than for residents | Guards turn away visitors | ||

| Additional restrictions on nonresidents during the pandemic |

Certain patterns emerge when analyzing municipal beach access policies. Different levels of restriction tend to appear in communities with specific demographic and geographic features. Wealthier and whiter areas, especially those neighboring more racially and economically diverse areas, tend to be far more restrictive, and place with large populations of people of color and working-class residents tend to have open access.

In exurban areas, isolated from Chicago and other cities such as Gary, Indiana, these patterns do not hold. Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin, for example, is mainly white and middle-class, with no transit connections to Chicago. Its beaches are free and open.

Within about an hour's drive from Chicago, the whitest municipalities tend to have the most restrictive access policies, while diverse municipalities tend to have more open beaches. Source: American Community Survey data.

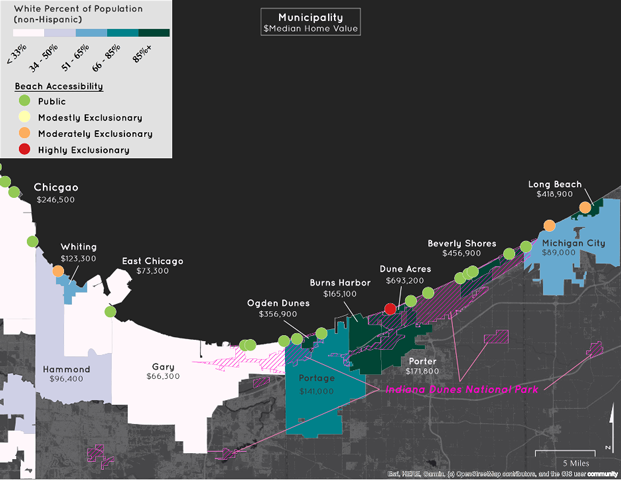

Open beaches appear in virtually every municipality with substantial Black and Latino populations. Chicago, with two-thirds of its population Black, Latino, or Asian, boasts 24 beaches freely accessible to the public—along a lakefront park system declared "forever open, clear, and free" in 1836. North Chicago and Zion, Illinois, and East Chicago, Gary, Portage, and Porter, Indiana, also boast free and open beaches and large populations of color.

Beaches run by county, state, and the federal governments, which represent a wider constituency, also tend to be open and not charge for admission. In the Indiana Dunes National Park, for example, beaches charge no fees. Municipally administered open beaches include exurban and rural towns with few transportation connections to Chicago, such as Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin.

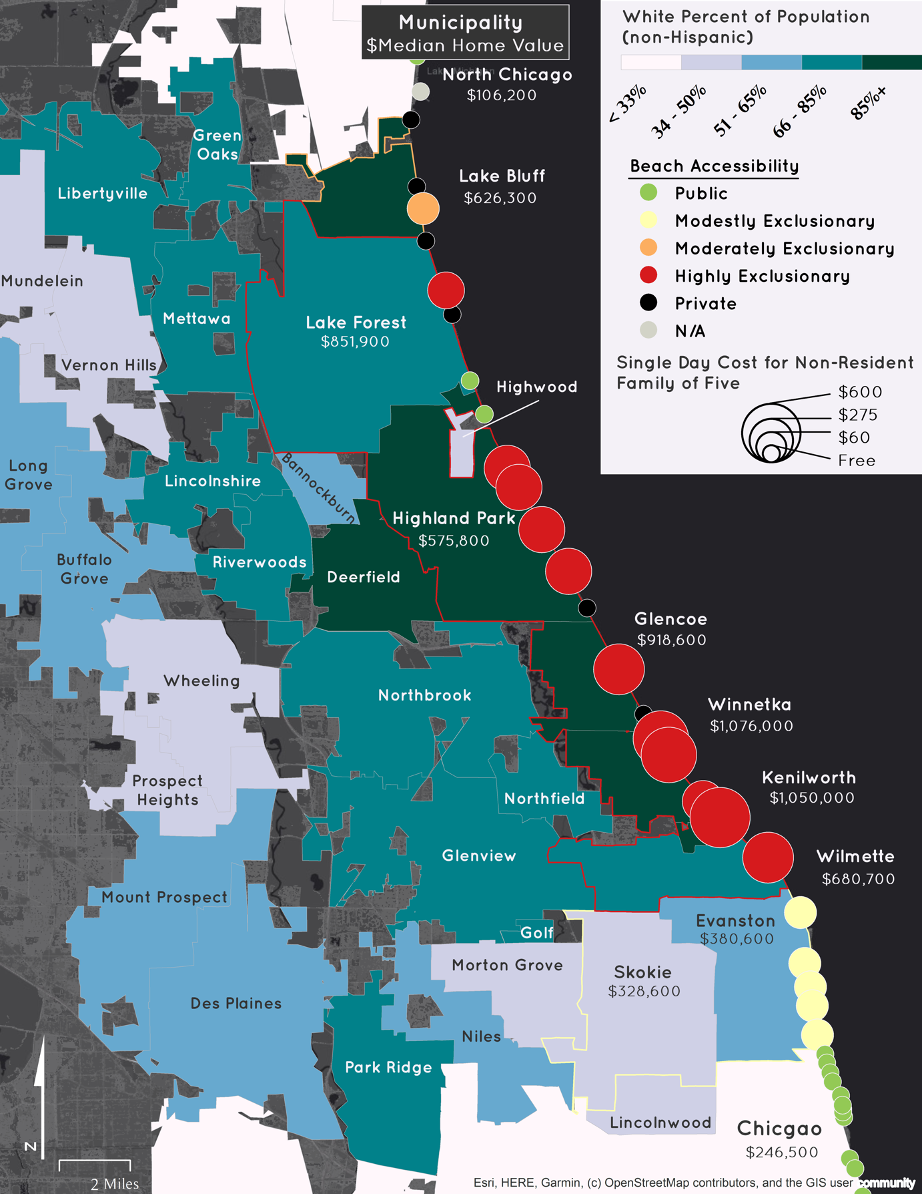

The beaches least accessible to nonresidents, labeled highly exclusionary, appear exclusively in affluent suburbs with predominantly white populations. Most of the municipalities are in Chicago's wealthy North Shore: Lake Forest, Highland Park, Glencoe, Winnetka, Kenilworth, and Wilmette, each of which charge fees $125 or greater for a day visit by a family of five.

Outside of the North Shore, municipalities use other tactics to discourage non-residents from visiting beaches. Dune Acres, Indiana, charges no fees but uses other means. Only one road leads into the town, protected by a security booth whose guard turns away nonresidents. In 2006, a Chicago Tribune journalist was told—falsely—that the beach was private, and was tailed by a security guard as he drove through the village. When an author of this report visited in August 2020, the guard turned away arriving vehicles, telling drivers, "There is no access." (Cyclists were observed entering without being hassled, presumably on the assumption that they will not visit the beach.)

Parking restrictions in Dune Acres make beach access essentially impossible for nonresidents, and vehicles without parking stickers are assiduously towed. No transit serves the area. On a sunny Saturday afternoon, the author arrived to find the Dune Acres beach nearly empty, the parking lot vacant except for one vehicle, and only two other visitors on the beach. Moderately exclusionary beaches include those in Lake Bluff, Whiting, and Michigan City. In Michigan City, for example, non-residents are charged $15 per day for parking while residents are not charged. Whiting, Indiana, charges residents $10 for a season parking pass and non-residents $100, but also offers day parking to residents and non-residents alike for $4/hour. The city’s beach has closed during the pandemic. Places with modestly exclusionary public beach access include Evanston and Waukegan.

On Chicago's wealthy, predominantly white North Shore, highly restrictive policies abound. Highly exclusionary North Shore suburbs have Black populations between .1% and 2%. Source: ACS data.

In Indiana, state and national parks offer open beach access along much of the shoreline. Source: ACS data.

Evanston, the most racially and economically diverse North Shore suburb, charges for beach access—between $30 and $44 for a nonresident season pass. But its fees are far lower than other North Shore suburbs, and only $12-$16 more than residents' access fees.

In addition, Evanston has several programs intended to improve beach access. It has a reciprocal agreement with Skokie to allow residents to use both towns' pools and beaches at reduced rates. The city also offers fee assistance programs to low-income residents and youth ages 13-18.

Waukegan charges non-residents $10 per car for parking on weekends and holidays.

Strategies of Exclusion

Highly exclusionary municipalities use a range of strategies to restrict access to public beaches.

In most municipalities, beach access fees and parking restrictions serve as the main tools to restrict access. Lake Forest, Illinois, for example, charges non-residents $25 each to enter Forest Park Beach, payable only by credit card, and does not offer a season pass for nonresidents.

Parking on-site requires a City of Lake Forest residency sticker, but nonresidents may purchase an annual beach parking sticker for $910. Daily parking passes are not available. The nearest public parking according to the Department of Parks and Recreation, is located in downtown Lake Forest, 1.3 miles away—a near thirty-minute walk which involves descending a steep bluff.

To visit Lake Forest's beach one time would cost a family of five $125. If that family were also to park nearby, the upfront cost would be $1,035, with an additional $125 paid for every additional visit. To visit Kenilworth Beach, that same family would have to pay $600 for a season pass—an increase of $395 over 2018's rates. The village does not offer day passes in 2020 because of the pandemic.13

Other, more subtle policies also work to keep outsiders out. At Sunrise Beach in Lake Bluff, for example, non-residents may enter only from 3-7PM—in addition to charges of $10-15 per day—while residents may arrive as early as 9:00am.

An entrance for residents only at Forest Park Beach in Lake Forest.

Many of the region's beaches are actually well-served by transit, especially on Chicago's Metra-lined North Shore. But in towns where commuter rail stations are far, such as in Lake Forest and Dune Acres, beaches lack transit connections.

Residential Segregation

Because of the demographic makeup of these municipalities, beach access policies which favor residents and exclude nonresidents have stark racial and economic ramifications. Regionwide in 2018, non-Latino whites made up just over 50 percent of the population; the Black population stood 16.4%, and the Latino population at 22.4%.14

Highly exclusionary municipalities do not reflect this diversity. Each has a non-Hispanic white population of greater than 80 percent, and none has a Black population higher than 2 percent. Dune Acres, Indiana, has a non-Hispanic white population of 98 percent. Kenilworth's non-Hispanic white population stands at 92 percent; Winnetka at 90 percent. In both Winnetka and Dune Acres, the Black proportion of the population was reported as one-tenth of one percent.

This residential segregation, particularly pronounced in northern metropolitan regions, is no accident, but instead the result of a decades-long, well-documented mix of racist policy choices and business practices. These include redlining and race-based financial disinvestment by banks, racial steering by real estate professionals, restrictive covenants, race-based harassment, zoning restrictions, and fierce opposition to affordable housing, among other factors.15

By basing access to the region’s shoreline on local residency, shoreline municipalities thus extend the historical race-based barriers to housing into the management of public space.

Residency requirements again point to the racially discriminatory features of beach access restrictions: racist in their origins, in their mechanisms, and in the racial disparities they exacerbate.

The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Chicago's Mayor, Lori Lightfoot, shut down Chicago's beaches during the COVID-19 pandemic. While intended to reduce the spread of COVID-19, these measures posed new challenges. In Chicago, site of a disastrous 1995 heat wave, the closures made inaccessible a significant piece of the city’s cooling infrastructure, already hobbled by pandemic-related restrictions on cooling centers and closures of air-conditioned storefronts and businesses.

At the same time, many suburban municipalities have kept beaches open to residents but implemented additional restrictions on nonresidents. Kenilworth, Highland Park, and Evanston no longer offer day passes because of the pandemic. (Some suburban beaches also shut down entirely in the pandemic, such as in Whiting, Indiana.)

Above, a security guard turns away visitors to Dune Acres, Indiana. Below, Dune Acres' quiet beach on a sunny Saturday afternoon in August.

Chicagoans, unable to visit their own beaches, have also seen their ability to visit suburban beaches dwindle even further with the pandemic. Rather than limit access on a first-come, first-serve basis or other means, many municipalities treat their beachfront public lands essentially as the private property of town residents.

The Environmental Dimensions of Walled-Off Beaches

In the Great Lakes region, shoreline municipalities face the growing threat of erosion and flooding exacerbated by climate change. In many ways, these threats have already worsened regional inequality and will continue to do so. But they also offer a mechanism to make beach access fairer. As municipalities depend more on outside funding for erosion and flooding mitigation, state and federal governments can—and should—mandate that municipalities that accept their money open their beaches to the entire public.

Beaches are on the front line of Lake Michigan's increasingly volatile water levels: they are the first areas on the shoreline to flood and are especially vulnerable to erosion. Already restricted and inequitably administered, beach land will become scarcer without intervention. Several climate-related trends—including increased precipitation and decreased lake ice in winter, leading to more evaporation—make forecasting lake levels challenging, but scientists predict fluctuations in lake levels to intensify in the coming decades.16 This variability will likely have disastrous consequences for shoreline erosion and flooding.17

Thus far, many municipalities have responded to these threats with parochial measures that protect local beaches and local residents to the detriment of the region. One strategy, for example, has been to armor the shoreline with seawalls and jetties to trap sand and protect against waves. First, these barriers have a detrimental effect on beaches down shore by prevent sand from depositing there - often inducing additional construction of artificial barriers, one after another, in an endless line along the shore. They also speed up erosion by preventing sand from being replenished. Second, they further restrict access to the shoreline. When lake levels go down, the armoring structures remain, preventing the public from walking down the shoreline. Thus municipalities' local decisions about the shoreline have regional consequences.

Suburban leaders may argue that local contributions to beach management justify high fees and limited access for nonresidents. But municipalities already depend on oversight and resources from higher levels of government to combat these threats, and are likely to do so even more in the future. When Highland Park renovated Rosewood Beach, for example, it did so with the oversight and approval of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and the Army Corps of Engineers. Federal legislators are currently considering the STORM Act, a $300 million fund for municipalities confronting Great Lakes flooding and erosion—problems exacerbated by local armoring. Another federal program is providing nearly $2 million in funding to prevent erosion to four municipalities, ranging from open to highly exclusionary: Evanston, Glencoe, Lake Bluff, and North Chicago.

When restrictive municipalities accept this money, they take a public regional environmental and recreational resource, manage it with state and federal resources and public tax dollars, and wall it off into local units that tend to exclude much of the public these spaces are meant to serve.

With lake levels growing more volatile, state and federal governments are likely to become even more financially involved with improving local beaches. When larger government units fund local beach improvements, they can cut through discriminatory access restrictions by stipulating municipalities open their beaches in exchange for funding.

Recommendations

1. Eliminate exclusionary beach access policies for nonresidents and use fair tactics to control crowding.

On summer weekends and holidays, municipalities may need ways to prevent beach crowding—especially during a pandemic. But implementing exorbitant fees for nonresidents takes public money to create essentially private spaces. These practices are racist in their origins and racist in their effects. They exacerbate environmental inequalities based on race and class.

Other strategies can limit crowding without discriminatory effects. A limit on the number of people on the beach at one time can serve the same purpose. If fees must be charged, approaches like those in Evanston and Waukegan might be considered: a modest parking fee for busy weekends, for example, or provisions for low-income people to access the beach free of charge.

2. Tie federal and state erosion protection money to open beach access.

In the 1960s and 70s, open beach activists sued several municipalities, arguing that those which accept federal or state money should not be able to use that money to maintain de facto private beaches. In 1970, the New York State Supreme Court struck down a ban on nonresident access in Long Beach because the beach had been built and maintained with federal funds. In New Jersey, Borough of Neptune City v. Borough of Avon-by-the-Sea (1972) established a similar principle.18

In response, some of the wealthiest suburbs in these states scrupulously avoided accepting state and federal money for beach improvements, thereby maintaining restrictive access. But this strategy is unlikely to remain viable as the cost of maintaining the present shoreline pile up.

Because of existing armoring and the growing volatility of Lake Michigan's water levels, even wealthy municipalities will likely have to accept state and federal money to maintain their beaches over time—thereby providing an avenue for opening access.

3. Manage the shoreline as a regional system.

Lake Michigan is an essential regional feature: a regional ecosystem, a regional natural resource, a regional source of recreation and economic activity, and the target of funding from regional and national sources. According to public trust doctrine, its shoreline is public land open to all. And yet too often, local, parochial interests determine how the shoreline is managed to the detriment of the region. Local armoring accelerates erosion elsewhere. Wealthy, predominantly white municipalities implement the harshest restrictions on access, whose effect is to keep out the region's nonwhite and the less wealthy residents.

Local management creates inequality in shoreline access. But a regional body can overcome parochialism, representing the interests not just of wealthy shoreline municipalities, but the entire breadth of the metropolitan region. That state- and federally administered beaches in the region are open shows the power of larger scales of government to overcome this parochialism.

4. Adopt a racial equity lens for shoreline access.

Restrictive beach access policies have origins in the racially discriminatory practices of the early twentieth century. A racial equity lens, an approach several cities have adopted in policymaking, would bring much needed perspective to the discriminatory features of shoreline management. A racial equity lens encourages policies that create equitable outcomes across racial lines - and asks how existing policies perpetuate and exacerbate racial inequality.

As historian Andrew Kahrl writes, "ostensibly race-neutral laws" long served as the foundation of beach access restrictions, even as the intention and effect of these laws has been to exclude African Americans and other racial minorities. Much of this same dynamic remains in place today, especially in Chicago’s North Shore. Access fees, parking fees, and parking restrictions all have disparate impacts on African Americans, other racial minorities, and working-class residents.

A racial equity lens also highlights the inequities of basing beach access on residency, a rule that extends the discriminatory practices of the housing market into public space.

5. Improve public transit access to public beaches

Many municipalities lack transit access to beaches, a barrier for people who do not own cars. For beaches to serve as open public spaces, they should be accessible to residents who rely on buses and trains to travel.

Conclusion

Beach access restrictions in Chicago perpetuate and exacerbate inequality along racial, economic, and geographic lines. Such restrictions have racially discriminatory origins and manifestations. They transform public land into de facto private land. As Lake Michigan’s water levels become more volatile, these restrictions are likely to intensify inequality in access to public shoreline. But the growing role of federal and state money in combatting erosion and flooding offers an opportunity to mandate local governments make their beaches more open and equitable.

- 1Andrew Kahrl, "Fear of an Open Beach: Public Rights and Private Interests in 1970s Coastal Connecticut" (2015): 434; also see Kahrl, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America's Most Exclusive Shoreline (2018).

- 2Kahrl, "Fear," 434.

- 3Kahrl, Free the Beaches, 15; 20.

- 4Kahrl, "Fear," 438-9.

- 5Arnold Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940-1960 (1983), 65-66; Virginia Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America (2012), especially 168-203.

- 6Kahrl, Free the Beaches, 21.

- 7Kahrl, "Fear," 450.

- 8Encyclopedia of Chicago, "Shoreline Development," interpretative essay.

- 9Wolcott, 38; 183-5.

- 10Wolcott, 35-6; 135-6. Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot (1922), 48.

- 11Wolcott, 185.

- 12Hirsch, 65-66.

- 13Author conversation with Kenilworth Department of Finance and Administration, August 25, 2020.

- 14American Community Survey data, 2018.

- 15See, for example, Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (2008); David MP Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America (2008); Amanda Seligman, Block by Block: Neighborhoods and Public Policy on Chicago’s West Side (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); NDB Connolly, A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014); Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto.

- 16Brent M. Lofgren, Timothy S. Hunter, and Jessica Wilbarger. "Effects of using air temperature as a proxy for potential evapotranspiration in climate change scenarios of Great Lakes basin hydrology." Journal of Great Lakes Research 37.4 (2011): 744-752; Andrew D. Gronewald, and Richard B. Rood. "Recent water level changes across Earth's largest lake system and implications for future variability." Journal of Great Lakes Research 45.1 (2019): 1-3.

- 17Guy A. Meadows, et al. "The relationship between Great Lakes water levels, wave energies, and shoreline damage." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 78.4 (1997): 675-684.

- 18Kahrl, "Fear," 452.