Post-Industrial Regions and the French Presidential Election

France's presidential election offers fresh insight into the relationship between post-industrial regions and partisan politics.

The recent French presidential election offers fresh insight into the evolving relationship between far-right politics and place, a phenomenon evident on both sides of the Atlantic. Although French President Emmanuel Macron once again defeated far-right challenger Marine Le Pen, the margin was appreciably closer than in 2017.

A component of this shifting political landscape is the changing partisan allegiances in post-industrial areas. Like much of Europe and North America, France is home to several regions where industrial and manufacturing employment has declined in recent decades. Far-right candidates—including Le Pen—have been buoyed by support shifting in their favor in these areas.

In France’s most recent election, however, this shift waned. While Le Pen again received some of her strongest support in areas that have experienced severe industrial job losses, her largest gains were in regions—the 13 large administrative units that make up Metropolitan France—with a less drastic history of post-industrial decline. Moreover, Le Pen’s support in post-industrial regions varied at the level of department (jurisdictions within regions), signifying a local political divergence similar to the United States Midwest.

Industrial Job Loss and Politics

Across all 13 of Metropolitan France’s regions, the share of employment in the industrial sector has declined over the past four decades (Table 1). Some regions, such as Hauts-de-France and Île-de-France (greater Paris), have experienced declines of 60 to 70 percent of such employment since 1975.

Table 1: Industrial Employment as a Percentage of Overall Employment

| Region | 1975 | 2014 | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 28.8% | 7.9% | -72.6% |

| Hauts-de-France | 39.0% | 14.9% | -61.8% |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | 19.4% | 8.8% | -54.6% |

| Grand Est | 37.4% | 17.1% | -54.3% |

| Auvergne-Rhône-AIpes | 34.9% | 16.2% | -53.6% |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 35.5% | 17.7% | -50.1% |

| Occitanie | 20.0% | 10.8% | -46.0% |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 30.0% | 16.6% | -44.7% |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 22.5% | 12.5% | -44.4% |

| Normandie | 30.3% | 17.0% | -43.9% |

| Pays de la Loire | 26.9% | 16.9% | -37.2% |

| Bretagne | 17.6% | 14.4% | -18.2% |

| Corse | 6.4% | 5.6% | -12.5% |

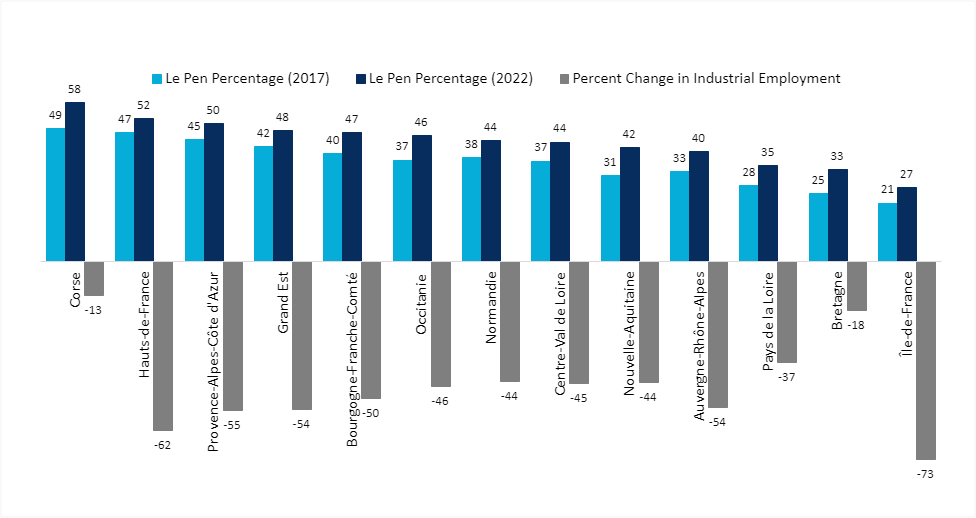

When comparing industrial job losses to Second-Round Presidential voting in 2017 and 2022, Le Pen received strong support in several former heavily industrial regions, most notably in the northern regions of Hauts-de-France and Grand Est (Figure 1). Likewise, she received tepid support in some regions without as strong a history of manufacturing and industry (and thus fewer job losses), such as Pays de la Loire and Bretagne. However, the relationship is not linear. Le Pen underperformed in other regions with strong industrial histories, such as Île-de-France and Auvergne-Rhône-AIpes.

Figure 1: Le Pen Support by Region and Change in Industrial Employment

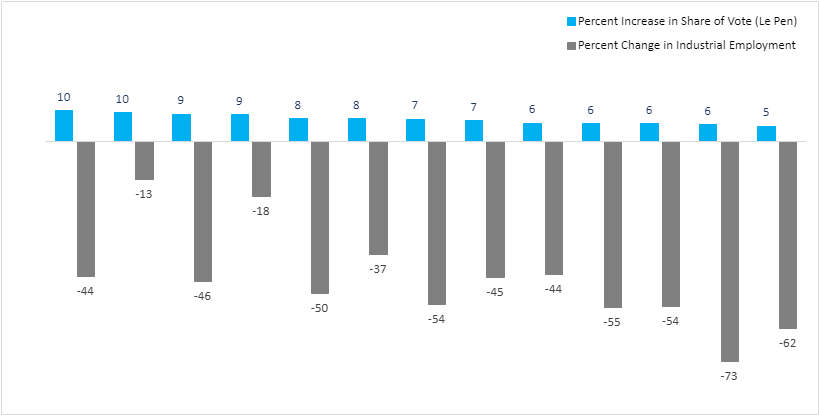

By analyzing the increase in support for Le Pen from 2017 to 2022 by region, a clearer picture emerges (Figure 2). Almost universally, Le Pen’s largest gains were in regions with a smaller percentage of industrial job loss. This suggests that Le Pen’s support broadened across France in 2022 for cultural, historical, or demographic reasons beyond the economic dislocation of deindustrialization.

Figure 2: Percent Increase in Le Pen Support and Change in Industrial Employment

Departmental Variation

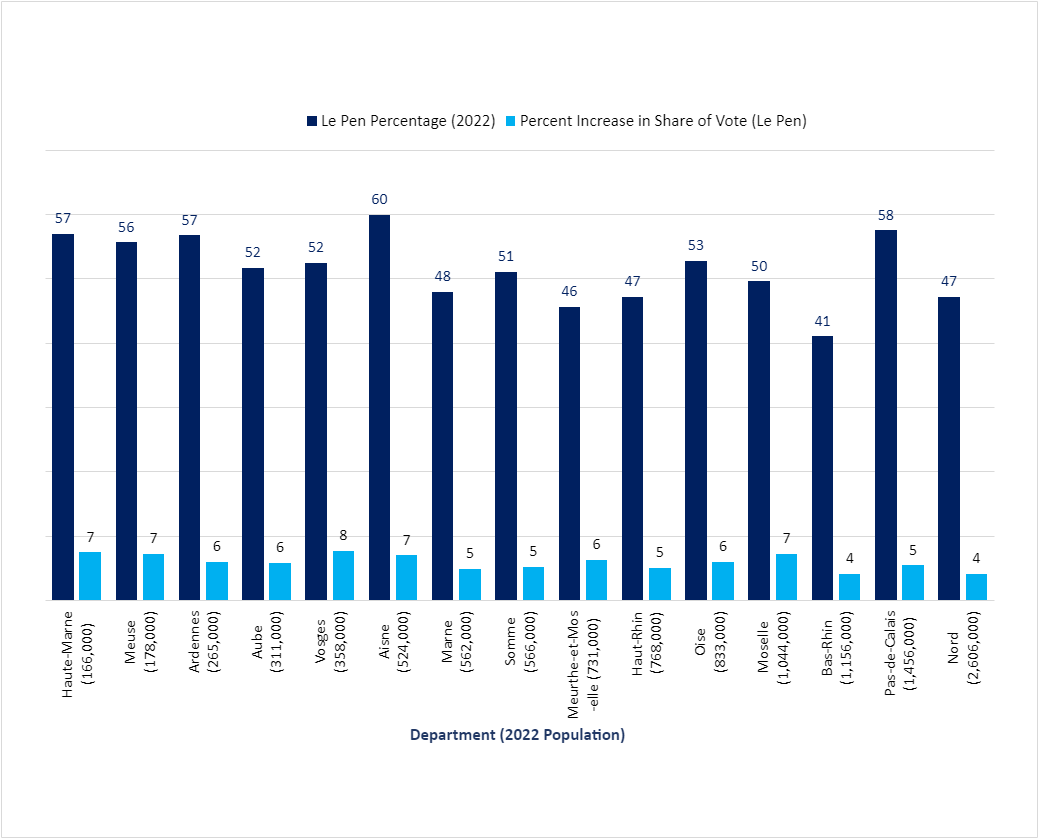

Two regions that reflect characteristic components of industrial decline and economic restructuring, Hauts-de-France and Grand Est, supported Le Pen in 2017 and 2022 by greater margins than the overall French electorate, and provide strong examples to analyze at the department level.

There was considerable variation in support for Le Pen in 2022 within the 15 departments of these regions, particularly between more urban and rural departments (Figure 3). In more densely populated departments, such as Bas-Rhin and Nord, and middle-sized departments such as Haut-Rhin and Marne, Le Pen’s support was less than in adjacent rural departments. This urban-rural demarcation mirrors the significant increases in support for Le Pen in many less-populated regions of France, most notably in the rural south.

Figure 3: Le Pen Support in Departments of Hauts-de-France and Grand Est

Reframing the Base of Far-Right Support

What does this suggest for the relationship between post-industrial areas and support for far-right candidates?

First, while support for Le Pen did grow in formerly industrial regions, it grew less than in other regions of France, demonstrating that support for far-right candidates is not limited to struggling, post-industrial areas.

Second, while certain post-industrial regions supported Le Pen more than others, her share was still below 50 percent of the total vote in each such region—Hauts-de-France notwithstanding. This may suggest that there is a potential ceiling for far-right support in such jurisdictions, or that far-right candidates may struggle to win over enough votes to offset losses in more populated regions, such as Île-de-France.

Finally, local variability within regions is great, with Le Pen’s support ranging from 40 to 60 percent of the vote across departments in Hauts-de-France and Grand Est. Tellingly, most departments that supported Le Pen are smaller in size, more rural, and lack large cities. This could suggest that there is a divergence of outcomes within regions, as certain communities—often larger cities—have found a way forward in a globalized economy, while hinterlands continue to struggle. Such findings suggest that focusing economic development efforts in communities with greater need can both blunt the appeal of extremist politics, while also developing more equitable outcomes for residents.

They also underline the reality that industrial decline certainly plays a role in support for far-right politics, but that other factors—cultural, historical, social—which have increased support for Le Pen (and other far-right candidates), must not be overlooked.