Generational Differences on US-China Relations

Younger Americans are more confident in US power vis-a-vis China and are more likely to oppose restrictions on scientific and educational exchanges between the two.

As past Council research into generational differences has shown, Millennials hold distinct views on a number of foreign policy issues, including climate change, the use of the military abroad, and drone strikes. In my last analysis in April 2020, I wrote that Council data showed “distinct and notable differences among the generations when it comes to China.” How much have these differences in opinion persisted through the huge shifts in US-China relations between 2019 and today?

Overall, American attitudes toward China have become sharply more negative across the board in recent years, and this includes younger generations. However, America’s youth are less likely to have made up their minds on US-China relations, are somewhat less likely to see China as a threat to the United States, and are more likely to oppose restrictions on scientific and educational exchanges between the two countries.

As in past work, we are using Pew’s definitions of the generational cohorts. Our current surveys include members of the Silent generation (born 1928-1945), the Baby Boomers (1946-1964), Gen X (1965-1980), Millennials (1981-1996), and Gen Z (1997-2012).

Younger Americans Most Confident in US Military Power but Least Confident in US Economic Power

Older Americans are having a bit of a crisis of confidence in US military power at the moment. In 2019, six in 10 Silents, Boomers, and Gen Xers all saw the US as the stronger military power. In 2021, all three groups have fallen under the 50 percent mark. The change has been especially dramatic for members of the Silent generation: a plurality now believe the US and China are about equal militarily. Interestingly, Gen Z looks a lot like the Silent Generation when it comes to this question: they are the most likely to say the US and China are about equal militarily (44%). These shifts have left Millennials as the most confident generation in American military power vis-à-vis China: a majority (51%) say the US is the stronger military power, the only generation where a majority says so.

When it comes to economic power, though, older Americans continue to have more confidence in American economic power than do younger Americans. Only two in 10 Gen Zers (18%) and a quarter of Millennials (24%) see the US as the stronger economic power. Millennials are the most likely generation to see China as the stronger economic power (43%). It’s also a plurality view among Gen X (41%) and Boomers (38%). And just as is true for views of military power, Gen Z is by far the most likely to see the two countries as evenly matched economically (44%).

Younger Generations Less Likely to Favor Restrictions on US-China Exchanges

These differences between generational groupings when it comes to views of China and the US-China relationship also carry over into views of US-China policies, outside of a few broad points of agreement. Majorities across generations support sanctioning PRC officials responsible for human rights abuses, and for negotiating arms control agreements between the United States and China. There’s also majority support for increased tariffs on imports from China.

Beyond that, however, generational differences emerge. And in general, older Americans are more likely to support restrictions on US-China exchanges, while younger Americans oppose them. For example, majorities of Silents (67%), Boomers (63%), and Gen Xers (60%) all support significant reductions in trade with China even at cost to US consumers, while Millennials are divided (50% support, 48% oppose).

The same pattern holds for scientific research and educational exchanges. Majorities of older generations favor restrictions on the exchange of scientific research, Millennials oppose such restrictions (56% oppose, 41% favor). Similarly, majorities of Silents (61%) and Boomers (57%) support limits on the number of Chinese students studying in the United States, while Gen X is split (49% support, 48% oppose) and a majority of Millennials oppose limits on Chinese students (65% oppose, 32% favor).

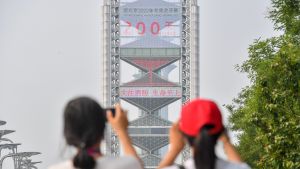

Interestingly, the major exception to this trend is an Olympic boycott. Majorities of Gen X and Millennials (55% each) support boycotting the Beijing Games over China’s human rights abuses, while Boomers are split (47% favor, 49% oppose) and Silents oppose a boycott (52% oppose, 42% favor). One factor in this may be the older generations’ memories of the last US Olympic boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games, and the subsequent Soviet boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Games. For more on that, see my piece in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage, which covers Americans views of Olympic boycotts past and present.

Because this question was split-sampled, we don’t have a large enough Gen Z sample to report their results with great confidence. The data we have suggests that Gen Z looks like Millennials in many respects, though they may be even more concerned about human rights issues than other generations of Americans.

Across Generations, Declining Views of China

Overall views of China fell sharply and with similar degree of decline across generational cohorts between the spring of 2018 and the summer of 2020, and views remained depressed into the spring of 2021. Comparing mean scores on the Council’s zero to 100 feeling thermometer item, where zero is the coldest score and 100 the warmest, all cohorts became sharply more negative on China between March 2018 and March 2021: Silents fell from 48 to 27, Boomers from 43 to 31, Gen Xers from 44 to 34, and Millennials from 48 to 34.

Because of the small sample sizes caused by a combination of split-sampling on individual questions and the overall small proportion of Gen Z who are adults, the data for Gen Z’s views of China over the same period are suggestive rather than definitive. For that reason, they are not included in the figure above (for this item, we have 41 Gen Z respondents in 2018, 53 in 2020, and 96 in 2021). But that data suggest Gen Z has experienced a similar drop in views of China, though less so than for older generations.

Results are similar when it comes to the US-China relationship more broadly—and for this question, we do have enough Gen Z respondents to get a sense of their opinions (though the sample remains quite small: 74 in this question). The most notable difference between generations is in the propensity of younger respondents to say they don’t know how to describe the US relationship with other countries: a quarter of Gen Z (26%) say they don’t know how to characterize the US-China relationship, compared to just five percent of Silents. Additionally, older Americans are more likely to view China as an adversary (36% Silents, 38% Boomers, compared to 27% each of Gen X and Gen Z, and 22% of Millennials). Another third across generations view China as a rival, with the exception of Gen Z (22%), and about two in 10 across generations view China as a necessary partner.

Skepticism of China’s intentions may be one factor driving these views of China as a rival or adversary for the United States, as majorities of Americans across generational lines say that China seeks to replace the United States as the most dominant power in the world. Gen Z is somewhat less likely to say so, and is more likely than older generations to say that China does not seek dominance regionally or globally (20%, compared to 15% of Millennials and one in 10 among older generations).

Older generations are more likely to say that China is more of an economic threat than a partner for the United States. Gen Z is the least likely to view China as an economic threat (57%, 43% see it as more of an economic partner). The generations are more unified in their view of China as more of a security threat than a security partner, though Millennials and Gen Z are somewhat more likely to view China as a security partner than are older Americans.

Related Research

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

2019 Chicago Council Survey data provide insight into how Millennials view key foreign policy issues compared with previous generations.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

Chicago Council Survey data reveals growing concern across party lines about China's economic and military power.