Are Millennials China Doves or China Hawks?

Data from the 2019 Chicago Council Survey and the Council's January 2020 omnibus poll show that there are distinct and notable differences among generations when it comes to China.

US-China relations

Over the past two years, US-China relations have taken a roller-coaster ride, marked by a bilateral trade war, dangerous naval incidents in the South China Sea, and an international fight over 5G networks and Chinese technology.

American views have, to a certain extent, followed these ups and downs in the relationship. In the summer of 2019, the annual Chicago Council Survey found that while threat perceptions of China among the overall American public remained fairly stable, that was not true for Republicans. For the first time since 2002, a majority of Republicans viewed the development of China as a world power as a critical threat to the United States. Yet by January 2020, with a Phase One trade deal wrapping up and a crisis with Iran dominating news headlines, Republican views of China as a threat to the United States had fallen back to previous levels.

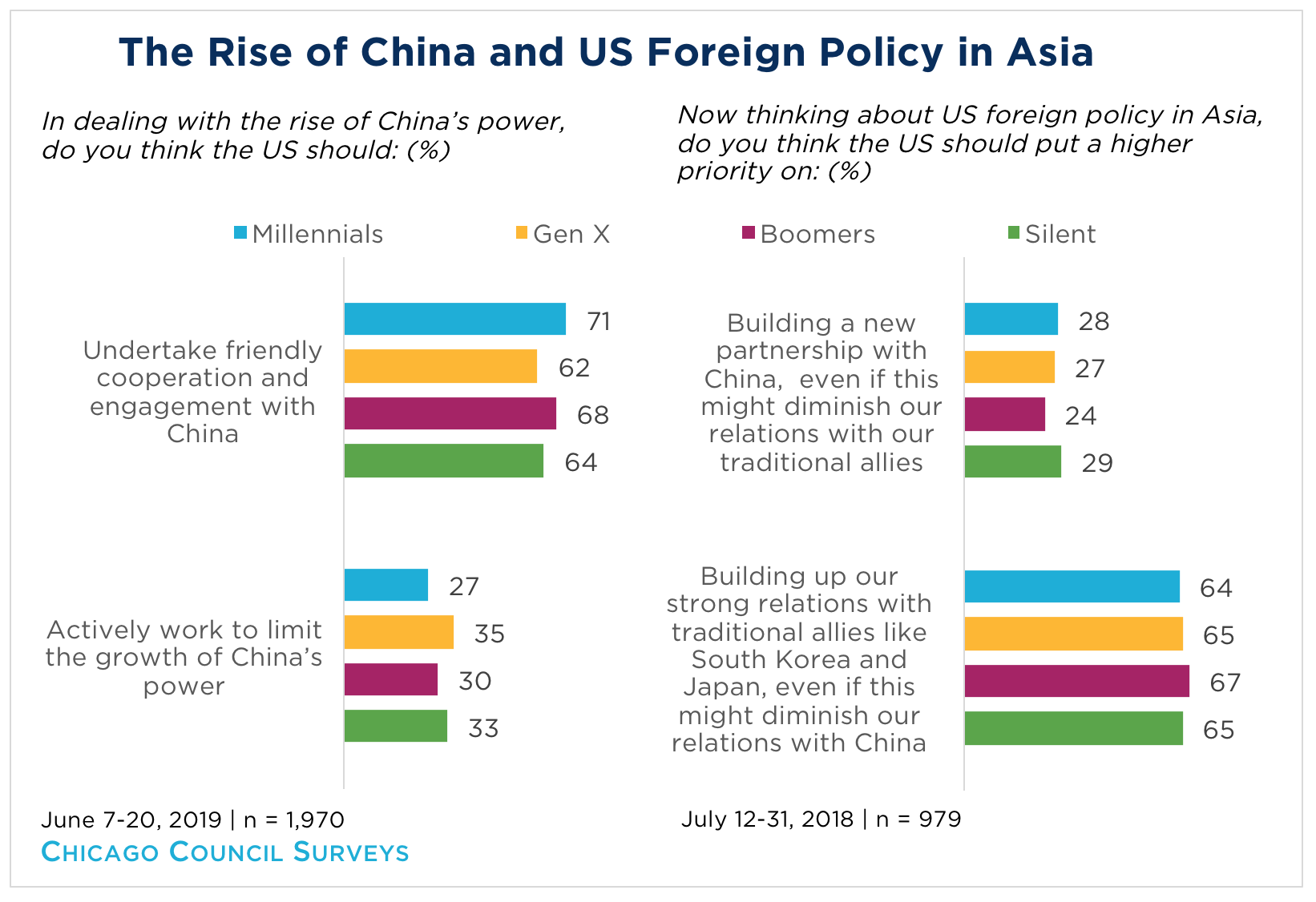

Despite divergent views of the US tariffs against China, there is great stability in other public attitudes toward China, with Americans generally hedging their bets in Asia. Since the Council first asked the question in 2006, Americans have consistently favored undertaking friendly cooperation and engagement with China rather than trying to limit the growth of Chinese power. At the same time, they have reliably favored strong relations with traditional US allies in the region to building a new partnership with China.

But how much of this holds true for Millennials? As other Council research has shown, Millennials hold distinct views on a number of foreign policy issues, including American exceptionalism, the use of the military abroad, and drone strikes. And data from the 2019 Chicago Council Survey and the Council’s January 2020 omnibus poll show that there are distinct and notable differences among the generations when it comes to China.

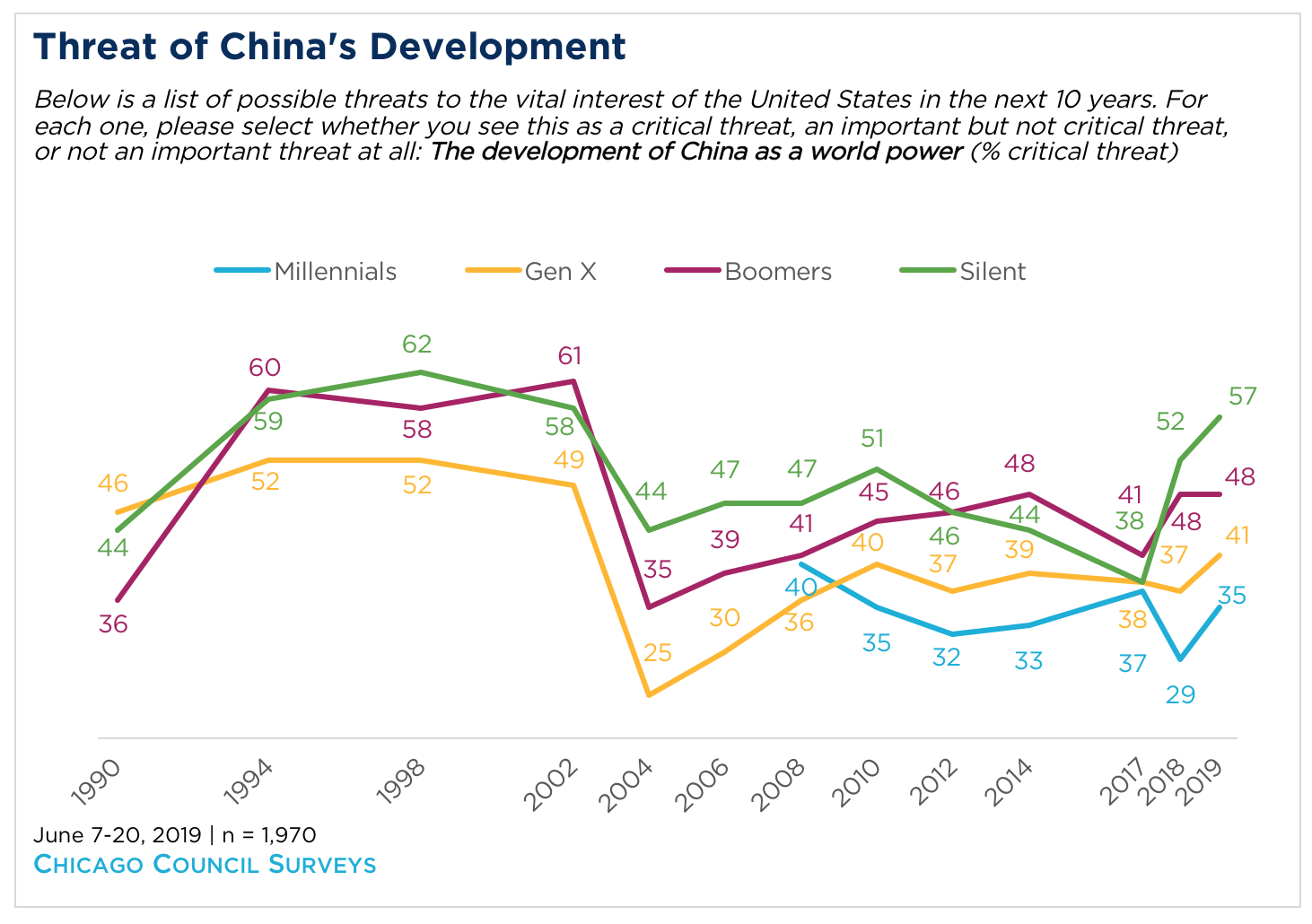

One of the most notable and persistent generational differences on China is on perceptions of China’s development as a threat to the United States. As the Council’s recent report on generational views points out, age gaps on perceived threats to the United States are common, with younger Americans usually less concerned than older Americans. In the 2019 Chicago Council Survey, these generational divides were largest on the threats posed by immigration, political instability in the Middle East, and the development of China as a world power.

Nor is the generational division over the threat of China a new development. The oldest generation of Americans—the Silent Generation, born between 1928 and 1945—have consistently been more likely than the Gen X or Millennial generations to name the development of China as a world power as a critical threat to US vital interests. By contrast, younger generations such as Gen X and Millennials have been less likely to see China’s rise as a threat. In fact, each successively younger generation is less likely to see China’s rise as a threat than the one before.

This played out very clearly in the 2019 Chicago Council Survey: 57 percent of Silents saw China's rise as a critical threat, compared to 48 percent of Boomers, 41 percent of Gen X, and 35 percent of Millennials. And while we don’t have quite enough Silents in our January 2020 poll to say for certain, the data we have suggests their concerns remain higher than younger generations even as overall concerns over China’s rise have leveled off.

Power

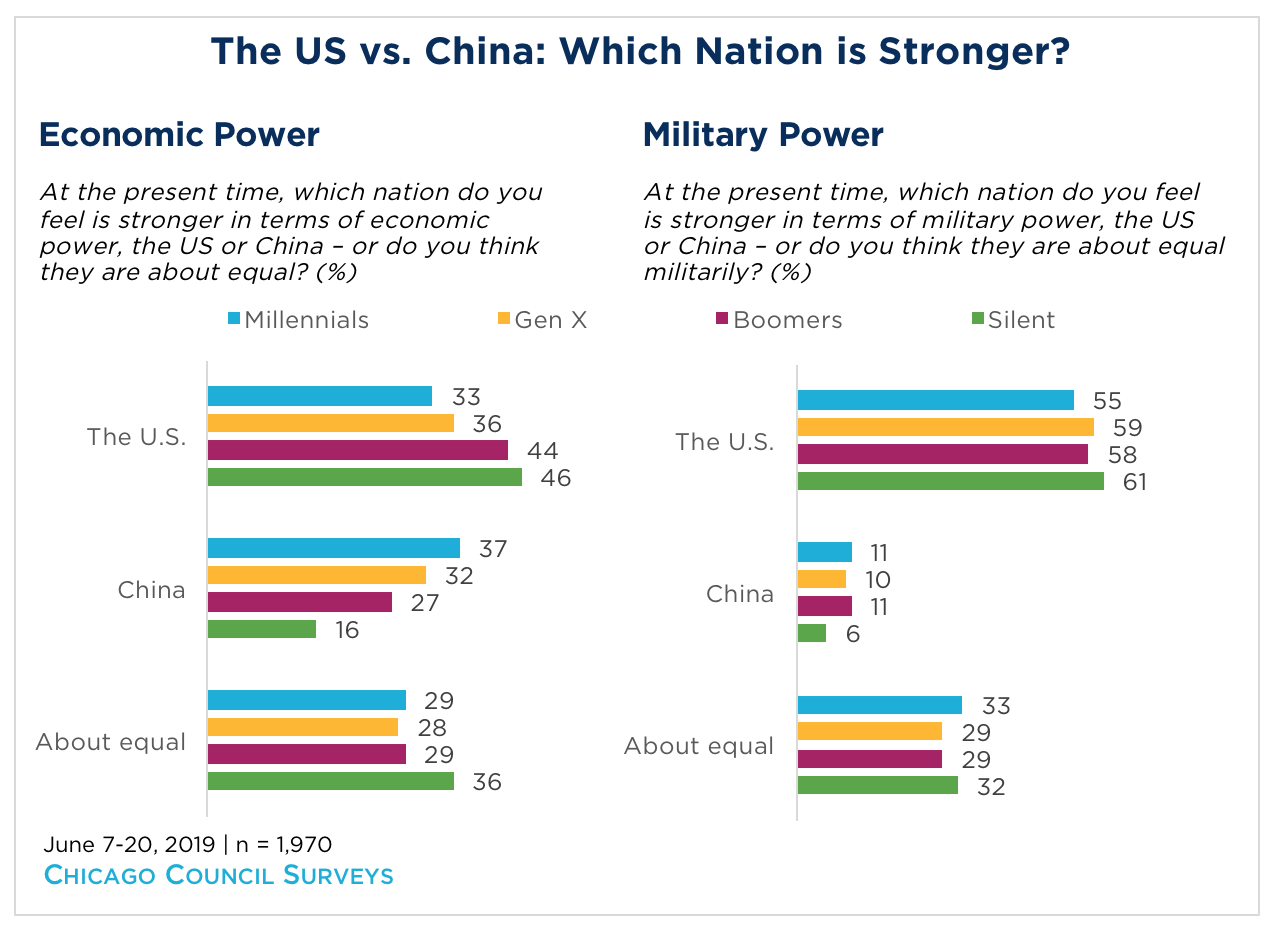

You might expect that older Americans’ concerns about China would be driven by a greater likelihood to see China as more powerful than the US, either economically or militarily. Interestingly, the opposite is true when it comes to economic power. In the 2019 Chicago Council Survey, older Americans are more likely to see the US as the greater economic power. Millennials, the generation least likely to see the rise of China as a threat, are about as likely to say that China is the stronger economic power as they are to name the United States. And despite these generational differences on Chinese economic power, majorities of Americans across the generations see the United States as the greater military power, with only one in ten naming China.

Policies

There are also a range of generational differences when it comes to US policy towards China. Millennials, like older generations, support the US negotiating arms control agreements with China and cooperating with China on international development assistance projects. But in other areas, Millennials stand out. Half (50%) favor inviting China to participate in joint military exercises, more than ten percentage points higher than all other generational groups. They are also notably less likely to favor placing tariffs on Chinese imports (40%) or restricting the exchange of scientific research between the United States and China, compared to half or more among other generations. And Millennials are the least likely of all generations to support selling arms to Taiwan (26%) or limiting the number of Chinese students studying in the US (28%).

But: Everyone’s Still Hedging

However, these generational differences have their limits. Despite a general interest among Millennials in cooperating with China on arms control agreements, international development projects, and military exercises, no generation is yet prepared to break from their traditional hedging posture in Asia. For one, no generation is interested in prioritizing a new partnership with China over the relationships with traditional US allies in Asia. When asked to choose in the 2018 Chicago Council Survey, roughly two-thirds across generations say the US should place a higher priority on building up strong relations with Japan and South Korea, even if it diminishes US relations with China. And at the same time, Americans across the generations favor friendly engagement and cooperation with China, rather than working to limit the growth of China’s power.

Conclusion

Interestingly, generational divisions on US-China policy are not only apparent among the public; they also appear to exist among policy experts. In June 2019, the Brookings Institution brought together several rising foreign policy scholars who focus on US-China relations for a long interview and discussion. As Brookings’ vice president and director of foreign policy Bruce Jones points out at the beginning of the discussion,

In the post-Cold War period, U.S. policy toward China was driven by a generation of scholars and experts trained during the Cold War and whose own careers were heavily shaped by the opening to China in 1978-79. The scholars in this interview, however, all turned to China in the period defined by China’s rise, not by China’s role in the Cold War.

Among policy experts, this different life experience of China seems to be leading to a generational split from older scholars and experts. As Ellen Nakashima reported last August in the Washington Post, the inaugural China forum at the 21st Century China Center “[took] place amid a generational shift.” As she described, “[a]n emerging generation of China policy experts is advocating a much sharper tone and approach toward Beijing, in contrast with a number of veteran China hands whose careers were shaped by the promise and tradition of engagement.”

Nahal Toosi, writing for POLITICO in July 2019, found a similar generation gap with older China hands afraid that “their approach might go extinct...These former officials, diplomats and scholars are wary about the rise of a younger foreign policy generation that is almost uniformly more skeptical of China, never having experienced the impoverished, isolated country it once was.” And, of course, young Chinese scholars have their own view of these divisions.

While these different generational experiences are also true for the public, the effects thus far are notably different. Born between 1980 and 1996, Millennials have never known a world without an open, reforming, rising China. But in contrast to many next generation policy experts, Millennials among the public are more likely than their elders to embrace dovish China policies, rather than hawkish ones. At the same moment that US policy is planning for a future of great power competition, the next generation of Americans seems notably unconvinced.