In Major Shift, Swedish Public Supports NATO Membership

Polling shows the Swedish public is keenly aware of the threat posed by Russia and favors a strong policy response to the invasion of Ukraine.

Sweden, alongside Finland, recently submitted a bid to join NATO as a full member after establishing itself as a neutral nation for more than 200 years. Stockholm’s refusal to formally join military alliances originated as a strategy to avoid both world wars and has since evolved into a central part of the country’s identity. Although Sweden has never been a full member of the alliance, it has cooperated with NATO on a number of occasions, including the Partnership for Peace program in 1994, the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council in 1997, and the 2009 inception of the Nordic Defense Cooperation (NORDEFCO). Following the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014, cooperation with NATO deepened—though such agreements and cooperative structures were mostly exercise-based, and confined to peacetime interventions. The social democratic government, historically and ideologically opposed to NATO membership, continued to assert that this security and defense policy cooperation was not, in fact, at odds with the official Swedish policy of military nonalignment.

Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February of this year, the Swedish government has significantly increased defense spending and strengthened ties to NATO. Sweden’s decision to remain militarily nonaligned has historically been popular with the Swedish public. However, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the direct threat it poses to Sweden’s security appear to have caused a significant shift in public opinion.

Sweden Uniquely Aware of Russian Threat

According to a March 25–April 3 Ipsos survey, Swedes are paying more attention to the invasion of Ukraine than any of the other European publics included in the survey, with 83 percent in Sweden following the events very or somewhat closely. Three-quarters of Swedes feel that the war poses a great deal or fair amount of risk to their country (75%). Among the European publics included in the survey, only Poles felt their country was more threatened (77%).

Swedish wariness of Russia is certainly impacted by geography and recent events, but also has deep historical roots. The Swedes lost significant amounts of territory in the 18th and 19th centuries in a number of conflicts with the Russian Empire, including the land that is now Finland. These conflicts resulted in the loss of Sweden’s Baltic Sea empire, and caused a sense of inherent threat from Russia to become deeply embedded in the nation’s collective memory. This history factors into both sides of the debate surrounding modern-day Swedish alignment. Some argue that the tradition of nonalignment, which began largely as a result of conflicts with Russia, should be continued, while others claim that the ever-present threat posed by Russia necessitates stronger security alliances.

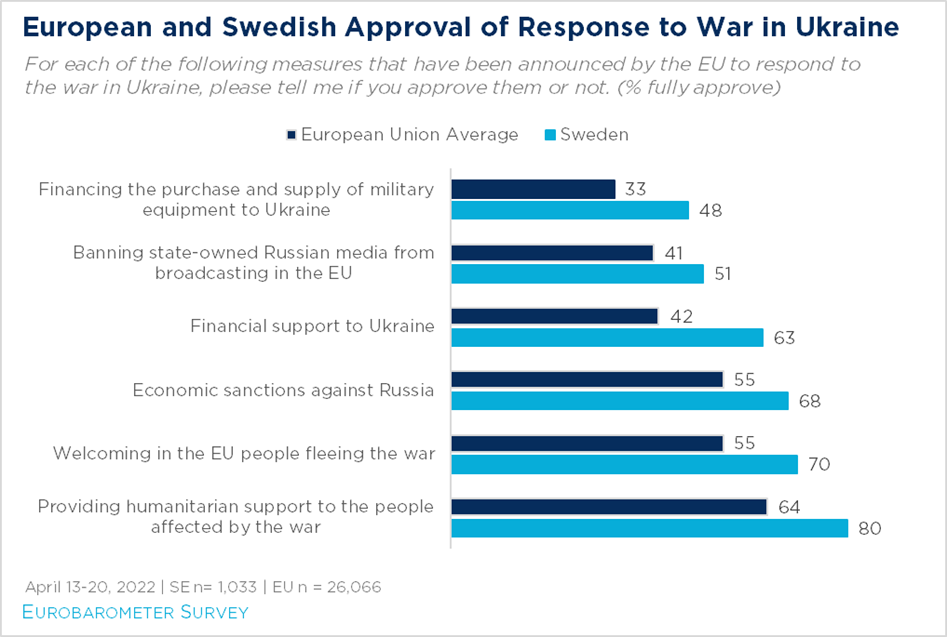

Partly in reaction to the increased sense of threat from Russia, the Swedish public is highly supportive of various policies that push back on Russia or support Ukraine. An April 13–20 Eurobarometer survey finds that, across the board, Swedes are more supportive of these policies than is average across the European Union publics surveyed. The Swedish public stands out in its support for financial support to Ukraine (+21% fully support compared to the EU average), providing humanitarian support to those affected by the war (+16%), welcoming refugees into the EU (+15%), and imposing economic sanctions against Russia (+13%).

Sweden's NATO Bid

The Swedish government has gone beyond actions to support Ukraine and increase pressure on Russia. Spurred by the recent Russian invasion, the Swedish government submitted a formal application to join the NATO alliance on May 18. A May 13–16 poll conducted by Novus reveals that more than half of Swedes are in favor of Sweden joining NATO (58%). This reading represents a slight increase from the May 4–10, when a Novus poll found 53 percent support for joining the alliance. These Novus polls are not anomalies—a Demoskop and Aftonbladet poll from March, also found a majority of Swedes in support of joining NATO (57%).

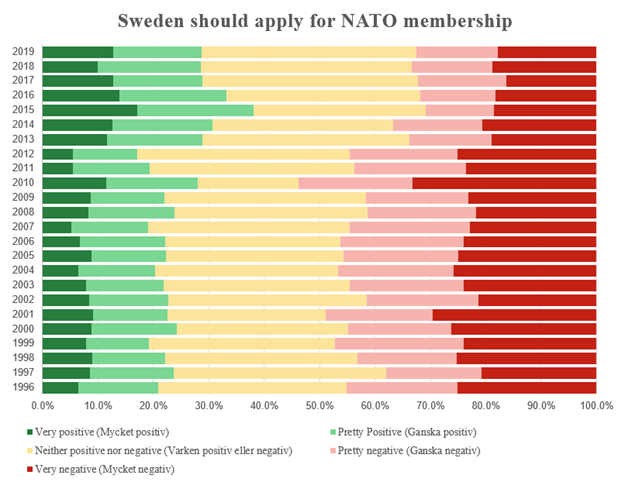

While these are slim majorities, they are significant given how consistently low Swedish support for NATO membership has been in the past. According to data from the SOM national survey conducted by the University of Gothenburg, Swedish public support for NATO membership hovered between 20 and 30 percent between 1996 and 2019, only briefly breaking into the 30–to–40 percent range between 2014 and 2016, following the Russian annexation of Crimea

Swedish support for eroding the historic policy of neutrality and military nonalignment was also low in 1994, when Swedes very narrowly voted for membership in the European Union. In the 1994 EU referendum, the two sides were separated by merely 5.5 percentage points—equivalent to roughly 295,000 votes. While these margins were undoubtedly narrow, the Swedish public has nonetheless generally remained supportive of the decision to join in the years since. In the political debate leading up to the May 2022 NATO application decision, the Left Party called for a similar popular vote, although one did not take place. The Left Party cited the need for a possible NATO application to be firmly anchored in broad public support and a clear democratic process.

In an interview with CNN, Swedish Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson directly linked Sweden’s application for NATO membership with Russia’s recent actions, characterizing the invasion of Ukraine as “illegal and indefensible” and expressing concern that Russia could attempt something similar “in [Sweden’s] immediate vicinity.” A similar sentiment was conveyed by Sweden’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Ann Linde: “Joining NATO is the right thing for Sweden’s security and for security and stability in our part of Europe,” she said as she signed Sweden’s formal request for NATO membership on May 17. This represents a serious shift from her party’s previous stance on the alliance. As recently as December 2021, Linde declared to Swedish parliament that a NATO membership was completely off the table. Similarly, a 2016 joint op-ed by the defense and foreign ministers argued that seeking NATO membership would be the “wrong way to go.”

Turkey's Objections

In order for Sweden’s application to be approved, all 30 NATO member states need to agree to admit the country to the alliance. This process was initially expected to go smoothly, considering Sweden’s long history of collaboration with NATO. “Our two militaries routinely exercise together. Your capabilities are modern, relevant, and significant. And your addition to the alliance will make us all better at defending ourselves,” said US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at a press conference welcoming his Swedish counterpart to the Pentagon on May 18. Despite US enthusiasm and endorsement of Sweden’s NATO application, Turkey has raised substantial objections that have significantly delayed the two Nordic countries’ accession processes. These objections have centered around Sweden and Finland’s alleged support for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and Gulen movement—insurgent groups that operate in Turkey and surrounding countries. These allegations stem primarily from the Nordic countries’ refusal to extradite members of these groups to Turkey.

While US officials and foreign policy experts expect these disagreements to be resolved and for Sweden’s membership bid to be approved, this delay has created an uncomfortable waiting period in which the Swedish public feels threatened by Russia. Meanwhile, the government has to rely on unofficial security assurances from the United States and its allies, rather than the more certain guarantees offered to full members of NATO. As a result of the uncertainty stemming from Turkish objections, a debate about withdrawing the NATO application has also surfaced in Sweden. A security and defense policy parliamentary review released to the public on May 13 also warned that, should Sweden voluntarily remain outside of the military alliance while Finland joins, they would be particularly vulnerable to possible Russian aggression as the sole non-NATO Nordic country.

Conclusion

In late June, NATO will be holding a summit in Madrid where leaders of each member nation as well as those that are partners of NATO will discuss the future security of the alliance. The conflict between Russia and Ukraine and its broader implications for the region are now central to that conversation. Sweden’s pivot towards NATO, both at the public and policy levels, is just one example of the transformational and lasting effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.