Has Economic Globalization Helped Great Lakes Cities?

Economic globalization has revitalized many once struggling cities (think New York, Singapore, Shanghai, and London) and created or re-created metropolises like Doha, Dublin, and Frankfurt.

Introduction

How have the leading cities in the Great Lakes region fared? Nearly every downtown area has been revitalized to bolster the local economy, but for metropolitan areas overall, economic performance has been mixed. Most large cities have outperformed their surrounding rural areas and outpaced smaller satellite cities that were built around old-line manufacturing. Yet, cities like Detroit and Cleveland continue to lag in their re-development, while others such as the Twin Cities, Indianapolis, and Columbus, are much further along the path to wealth and growth.

Population and per capita income provide an answer

Using population estimates for the Great Lakes metropolitan areas from the U.S. Department of Commerce (BEA) (all the way back to 1969), we can examine eleven large, historically prominent metropolitan areas that represent the backbone of the Great Lakes economy. The chart below indexes each area’s own population to a value of one starting in 1969 and tracks relative population growth to 2017.

This shows that first, there is marked dispersion in the population growth of these places. At the bottom, populations have declined markedly in metropolitan areas of Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and Detroit to a lesser extent. At the other end of the spectrum, population has soared in the Twin Cities, Indianapolis, and Columbus. Second, for the most part, this divergence began at the outset in 1969 and continued through 2017. By the end of this period, the Twin Cities population had grown 70 percent, while Pittsburgh and Buffalo had fallen 15 percent.

Per capita income offers a second performance yardstick. Income per person measures the overall annual resources that are earned by metropolitan residents through workforce earnings, government payments, and by earnings from capital and businesses.

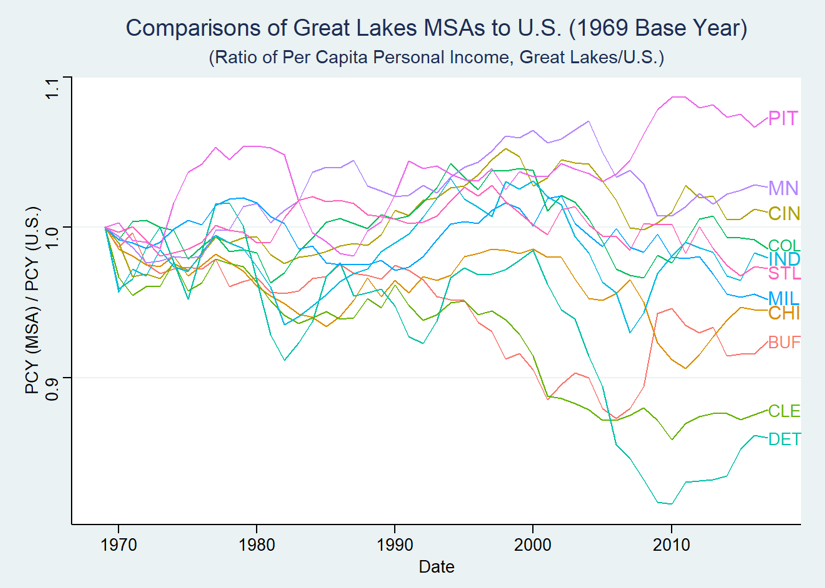

In the same time frame, 1969-2017, we can see each metropolitan area’s per capita income compared to the per capita earnings of the overall U.S. population. This analysis highlights changes in income growth over time compared to the United States average.

The chart shows a marked dispersion in performance, though not at the scale of differences in population growth. Most of the Great Lakes metropolitan areas have experienced declining average incomes in relation to the overall U.S. since 1969. For example, an index value of .95 for the Chicago metropolitan area in 2017 indicates that average per capita income relative to the overall U.S. has fallen 5 percent since 1969.

Yet, in this instance (and others), average figures on income hide important indicators of economic resurgence. Wealth and opportunity generating cities like Chicago attract immigrant and young workers with lesser skills and fledgling careers so that, at least at the outset, earnings of such workers tend to depress the average. Chicago’s workforce and population were buoyed by heavy immigration from the mid-1980s through the turn of the century before slowing markedly. In addition, young professionals have continued to flock to Chicago’s downtown and surrounding areas. A report on recent college grads found that the Chicago metropolitan area ranked only behind NYC as the favored destination of job-applying Midwest grads. Chicago’s central area has been ground zero for such job opportunities as college-educated millennials have increased by seventy percent over a recent 10-year period.

In what enterprises are the young workers finding jobs? Large corporate headquarters continue to move to Chicago from both the suburbs and from outside the metropolitan area. These include marquee names such as McDonald's, Caterpillar, Mondelez, and Dyson. Expansion of key business service facilities in accounting, consulting, insurance, and logistics have paralleled Chicago’s attractiveness to headquarters activities and points beyond.

Despite such promising developments, Great Lakes metropolitan areas that have fallen behind in growth in per capita income are generally also those with lagging population. At the bottom, we again find Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo. The theme here is that wages and earnings do tend to fall in places with moribund population and job growth.

Exceptions to these well-worn paths of declining population and income can be perhaps very telling in helping us further understand the mechanisms of growth and re-birth. Pittsburgh is a marked exception to the tendency of growth and per capita income to progress in similar direction. Remarkably, the Pittsburgh metropolitan area recorded the most severe population decline between 1969 and 2017. Yet, its relative per capita income outpaced every other Great Lakes metropolitan area, including the Twin Cities area. Pittsburgh, then, may represent the type of place that has been successful in shifting its old industrial economy to new industries like robotics, health care research, and computer programming. Yet, despite evident progress in average incomes, Pittsburgh is a much smaller place. What is the price progress?

Putting together these two measures of growth—population and per capita income—raises the question: where is the region headed? As the strong forces of globalization and technological change continue to play out, evidence from the varied Great Lakes landscape can be helpful for policymakers, businesses, and industries choosing how to adapt successfully in today’s economy. For many places, the choice between supporting an established industrial base versus turning toward a new one is as sharp as ever.

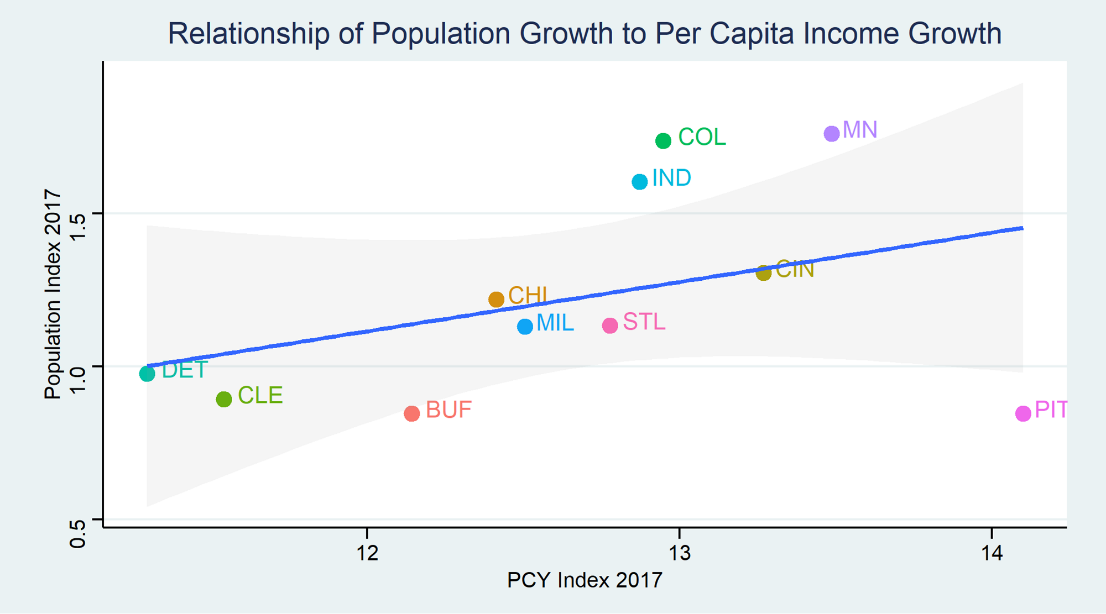

The chart below clearly shows that growth in population and per capita income generally go hand in hand. Were it not for Pittsburgh’s performance, it would be even clearer that the older industrial cities of Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo—all on the Great Lakes—are the region’s urban laggards. In contrast, the university-oriented and state-capital cities of Indianapolis, Columbus, and the Twin Cities have fared better in both income and population growth.

Are these places perpetually blessed due to their former non-manufacturing orientation? Or do they merely have a head start on their older industrial neighbors who will eventually catch up to them as they restructure their economic base? After all, being oriented in steel production as it once was, the Pittsburgh area arguably declined prior to cities with more auto and machinery-oriented economies. Perhaps prosperity can be just around the corner for the others.