While many Russians favor negotiating for peace with Kyiv, they are unwilling to give up any Ukrainian territory seized since 2014. They are, however, more open to a “neutral” status for eastern Ukraine.

A May 25–31, 2023, joint Chicago Council-Levada Center survey finds that many Russians would support ending the conflict in Ukraine and moving to negotiations, but few are willing to make meaningful territorial concessions to Kyiv. Focus groups among Moscow residents on April 20, 2023, help to contextualize this resistance.

Key Findings

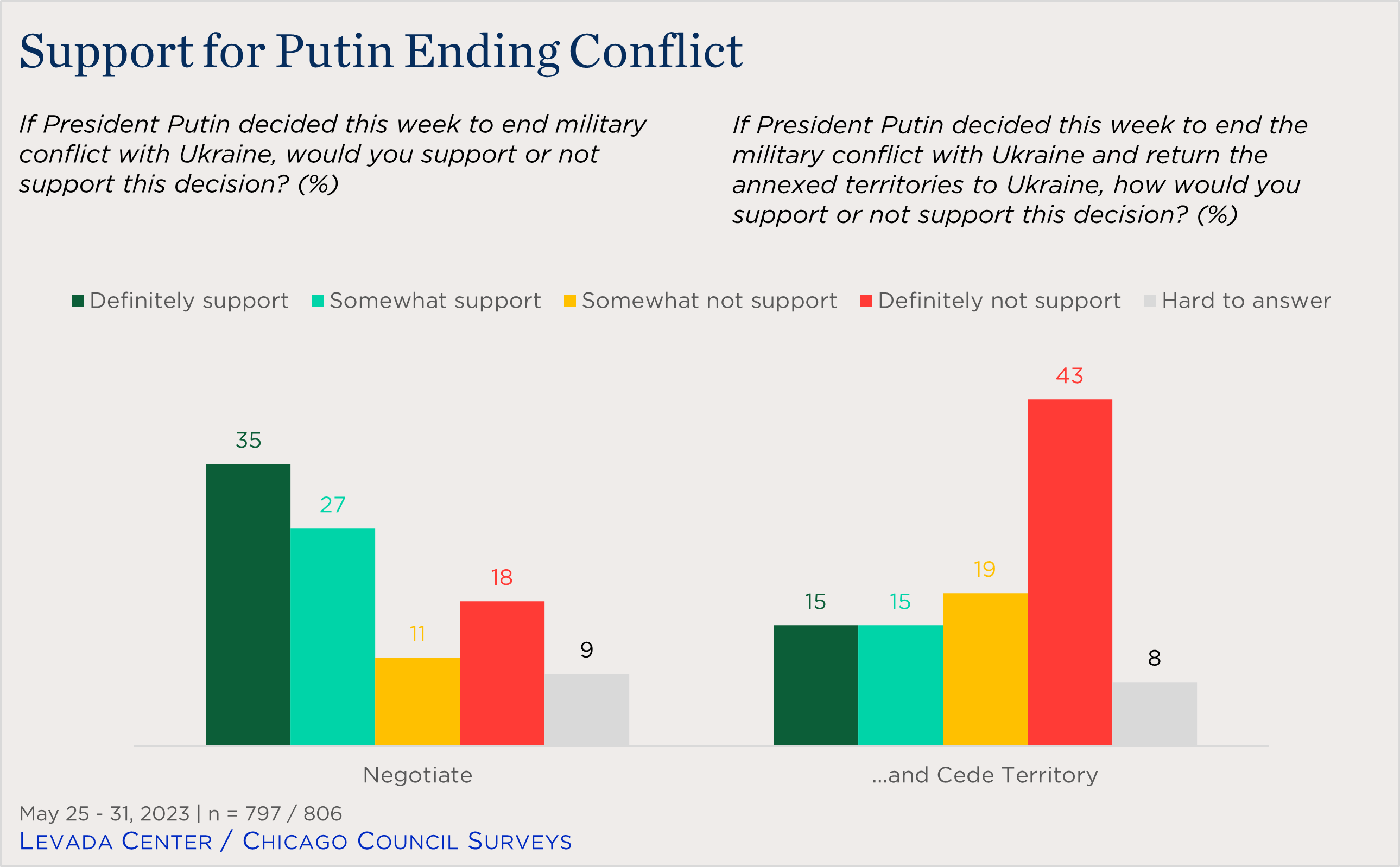

- Sixty-two percent say they would support Russian President Vladimir Putin ending the military conflict with Ukraine this week (35% definitely support, 27% somewhat support).

- But if ending the conflict this week were dependent on returning territory to Ukraine, the same percentage (62%) would oppose it.

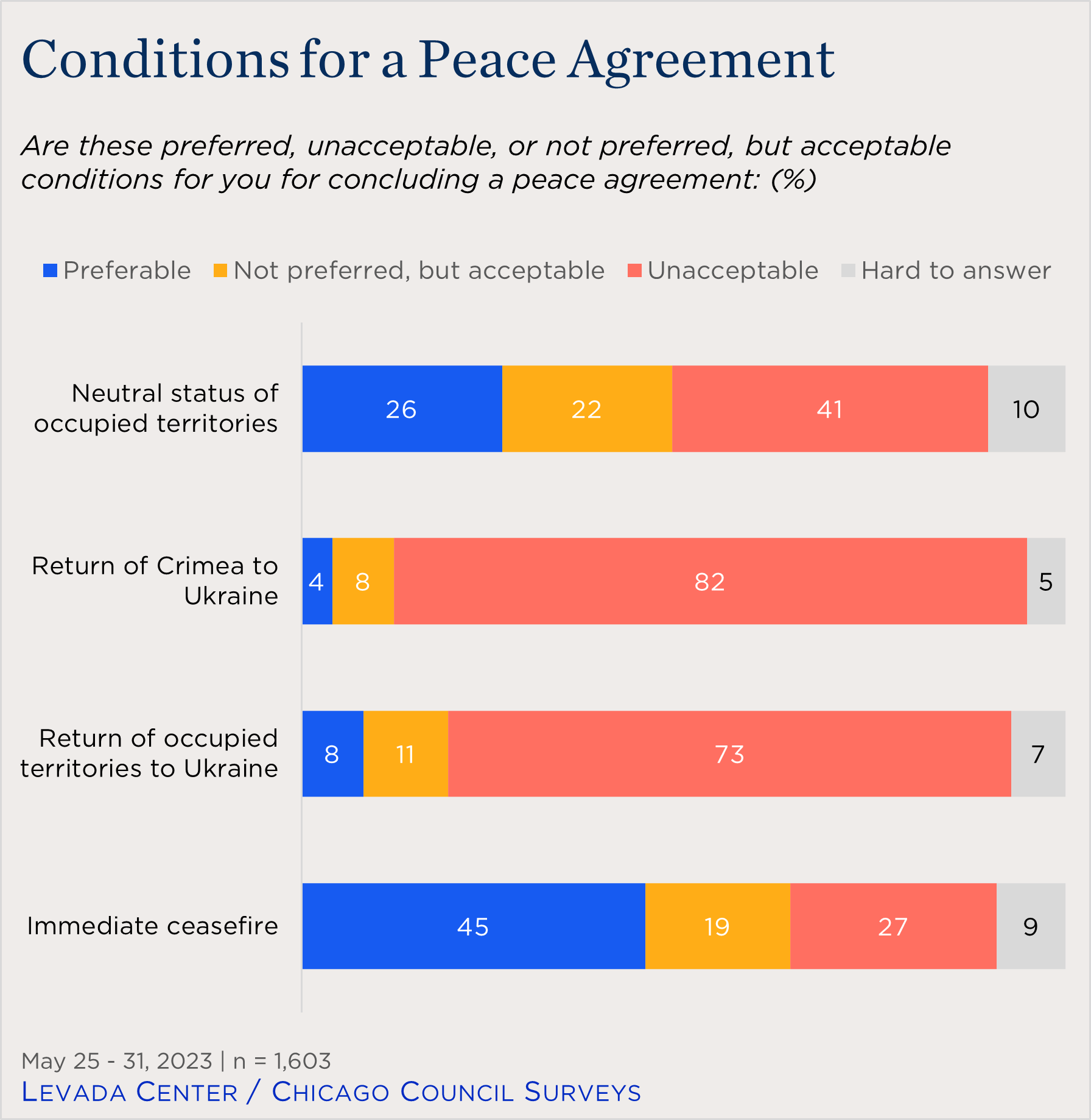

- Seven in 10 (73%) think that returning Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, or Kherson to Ukraine is unacceptable under any circumstances. Even more, eight in 10 (82%), would find returning Crimea unacceptable.

- Few Russians believe their country alone will have to make concessions (3%) to bring about an end to the war; 41 percent think both Russia and Ukraine will have to make concessions. And 39 percent think Ukraine alone will have to make concessions.

Continue Fighting or Negotiate?

The average Russian and Anthony Blinken may agree on one thing currently, albeit for wildly different reasons: there’s no possibility of a Russian-Ukrainian peace deal acceptable to both sides. A joint Chicago Council-Levada Center survey conducted May 25–31, 2023, finds more Russians now prefer to continue the “special military operation” (48%) rather than begin peace negotiations (45%). This increase in support for continued military action might reflect a combination of increased optimism after Russian military gains in Bakhmut in May and increased anxiety over attacks inside their own country.

In a separate question (asked of half the sample) that tests whether an announcement from Putin could influence support, 62 percent said that if the Russian leader decided to end the military conflict with Ukraine this week, they would support his decision (35% definitely support, 27% somewhat support). Four in 10 would oppose it (39%). Yet this support drops dramatically to just 30 percent when the other half of respondents were asked if they would support Putin’s decision to end the military conflict if it included returning annexed territories to Ukraine. Six in 10 Russians would oppose returning territory to Ukraine (43% definitely, 19 somewhat).

The May survey further supports this view. When asked about particular concessions in exchange for the cessation of fighting, two-thirds (64%) of Russians would find an immediate ceasefire and new borders on the frontline to be either a preferred outcome (45%) or an acceptable one (19%). Younger Russians prefer this ceasefire option more so than their older counterparts (51% among those ages 18-39; 42% among those 40 and above).

Large majorities oppose ceding conquered territory back to Ukraine. For 73 percent of respondents, returning Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, or Kherson to Ukraine is not acceptable under any conditions. Eight in 10 (82%) feel the return of Crimea would be completely unacceptable.

Focus group discussions underscored an unwillingness to consider outcomes that would entail returning territory back to Ukraine. One of the male participants said he preferred “a clean victory,” a “complete victory.” Another added “it must be finished once and for all, because if history teaches us something, it is that we can’t repeat the mistakes of the past.” Another man explained that victory would justify the action; there would be “a powerful surge of pride in society, and people [will] see that everything was not in vain and this would be worth all the losses, and the money spent, and so on.”

"It must be finished once and for all, because if history teaches us something, it is that we can’t repeat the mistakes of the past."

For many men, a complete victory entailed “full annexation [of Ukraine] to Russia, so that there are no incidents in the future.” Another man agreed: “I also think a positive scenario for [Russia] is a complete victory . . . complete disarmament, well, we completely unite Ukraine with Russia.” But at least one male participant said that if complete annexation is not possible, then “it is best to preserve what is [currently under Russian control]: Crimea, Luhansk, Donestsk, Kherson.”

Many women were also fairly unyielding when it came to territorial concessions. “Crimea is ours, and Donbass, the LPR [Luhansk], the DPR [Donestsk], it all remains with Russia. If this does not suit someone, then it turns out we will not have peace,” one woman asserted. Another woman described retaining the occupied areas as “a matter of honor for Russia to return [to Russia] the complete territories of the [Luhansk] and [Donetsk], as well as the Kherson region. To get back to us what we have already announced to everyone that this is ours.”

The survey further finds that just under half say granting Donetsk and Luhansk “neutral” status would be acceptable (48%), but four in 10 would find even that outcome unacceptable (41%). A female focus group participant thought this might be a possible outcome, predicting that “no one will get these disputed territories. They will have some kind of controversial status à la Kosovo.” Another woman also posited that neutral status might be a possible end goal for Ukraine. “It seems to me that Ukraine would go to the conclusion of peace only . . . on the condition that these new territories will have neutrality, some kind of neutral status. Otherwise, it would have ended long ago.” Another woman even suggested giving eastern Ukraine independent status: “Let them shoot each other with darts. Let Luhansk and Donetsk be separate countries, let them live as they want. Neither to us nor to Ukraine.”

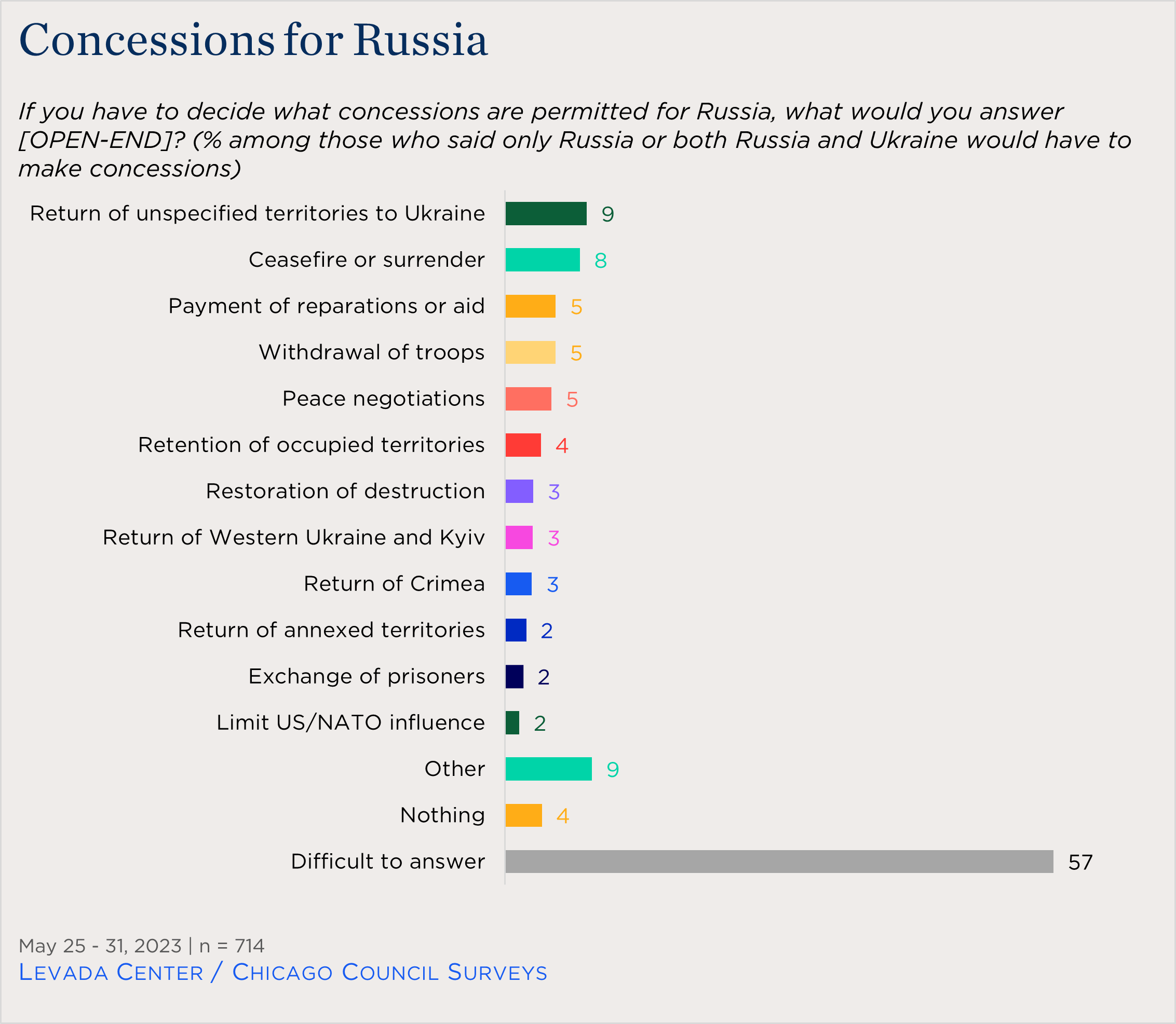

In an open-ended question about what concessions they would find permissible for Moscow to make, Russian respondents either struggle or are unwilling to name acceptable compromises. More than half say it is too difficult to say (57%). Not a single tangible response—from a prisoner exchange to returning territory—was put forward by 10 percent or more respondents.

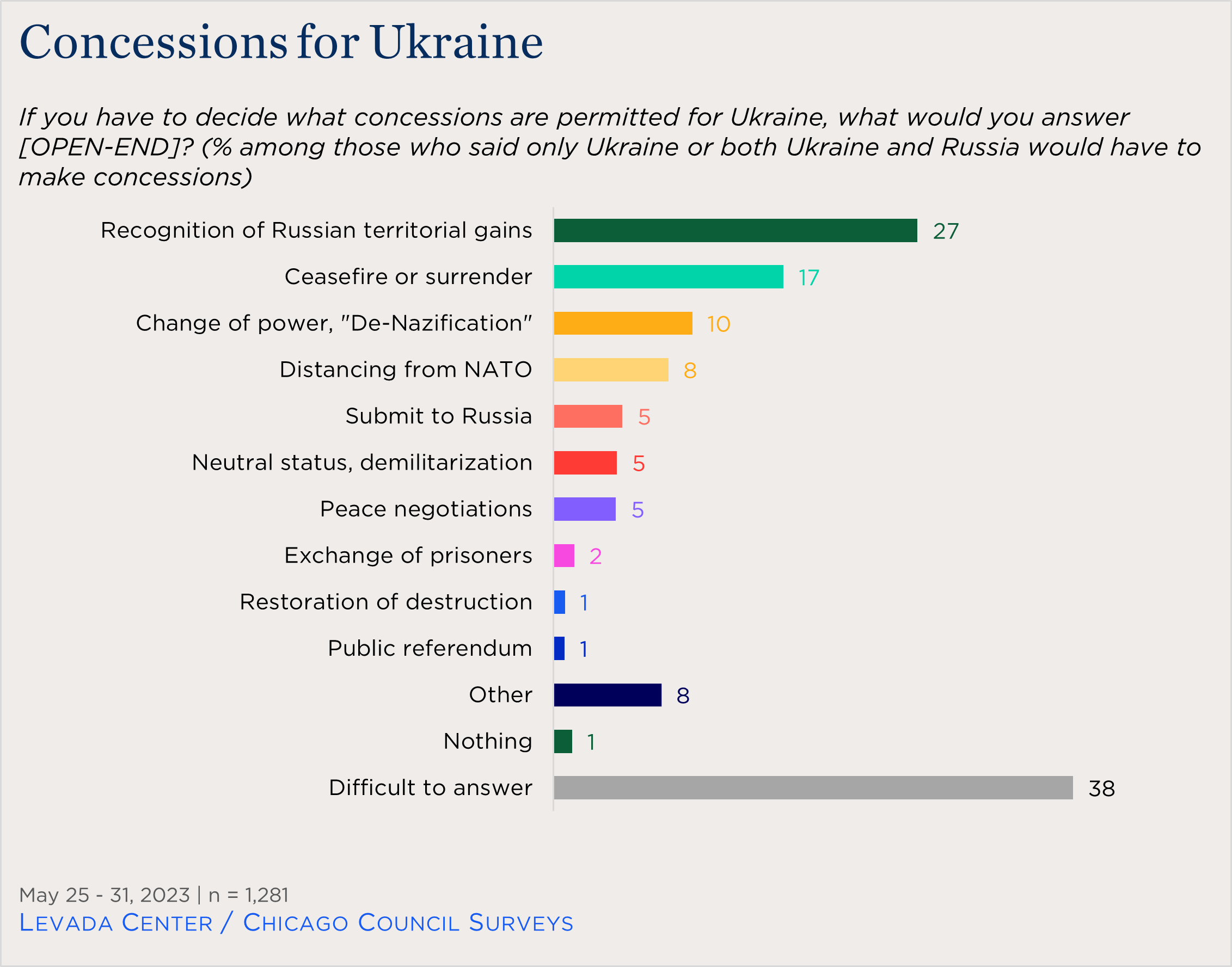

As for acceptable concessions Ukraine would make, Russians volunteer to the open-response question the top three suggestions of Kyiv’s recognition of Russian territorial gains (27%), surrender (17%), and change of power or “de-Nazification” (10%). However, a plurality say it is difficult to say (38%).

Most curiously, participants in both the male and female focus groups discussed the possibility of dividing up Ukraine, with western Ukraine going to Poland. This is likely due to claims made by the Russian intelligence service that this is Poland’s goal. As one man put it, “I do not think that the full annexation of Ukraine to Russia is the best outcome; it is unlikely that it will ever happen, much rather some part of Ukraine will pass to Poland.” One woman suggested that Zelensky himself does not want the borders to return to those prior to the annexation of Crimea because he “wants to give something to Poland.” Others suggested that Western countries and Russia would carve up Ukraine. One man elaborated, “Half of Ukraine, it seems to me, will go to the West, half to Russia, and the West will invest money in restoration.”

Which Side Will Have to Concede?

Few Russians believe their country alone will have to make concessions in the end (just 3%). Nearly as many Russians think both Russia and Ukraine will have to make concessions (41%) as think that just Ukraine will (39%). Even though focus group participants were unwilling to imagine an outcome where Russia would have to give up territory, one woman did acknowledge that an outcome without concessions from the Russian side would be challenging: “Russia will never give up the Donbass . . . Russia will not give up Crimea, so in principle, some concessions from Russia . . . are considered inappropriate. They won’t be easy.” And yet, most would prefer that other countries not participate in any negotiations on Ukraine’s future; a majority of Russians think the resolution of the conflict should be left to Ukraine and Russia to reach (72%). Just two in 10 (18%) think other countries should mediate an end to the conflict.

"The best scenario is a clean victory . . . Ukraine surrenders, the West ceases to stand up for it and supply weapons and anything else, they understand that it is better to solve it peacefully even if Russia wins."

Conclusion: Dim Prospects for Peace Talks that Russians Would Support

While many Russians say they would support ending the fighting and moving to negotiations, this is heavily conditioned on significant, if not complete, territorial concessions from Ukraine. This leaves little space for the Russian government to negotiate and creates yet another roadblock to ending this conflict.

This survey was part of Levada's monthly omnibus survey. Read the full methodology.

For this particular wave of the Levada Center's monthly omnibus survey, the interviews were conducted between May 25–31, 2023, among a representative sample of all Russian urban and rural residents. The sample comprised 1,603 people 18 or older in 138 municipalities of 56 regions of the Russian Federation (including Crimea). The survey was conducted as a personal interview in respondents’ homes. The answer distribution is presented as percentages of the total number of participants along with data from previous surveys.

The statistical error of these studies for a sample of 1,600 people (with a probability of 0.95) does not exceed:

- 3.4 percent for indicators around 50%

- 2.9 percent for indicators around 25%/75%

- 2.0 percent for indicators around 10%/90%

- 1.5 percent for indicators around 5%/95%

This work is made possible by the generous support of the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

The group discussions were conducted on April 20, 2023, at the Levada-Center’s Studio, among eight men and eight women aged 20 and older. Participants were selected by professional recruiters in Moscow using the “snowball” method through recruiters’ networks as well as those of previous participants of Levada-Center’s focus groups and were screened by age and gender. Any person who had participated in a focus group less than one year prior to this study and anyone who worked in the field of marketing or political and social sciences was excluded from the selection process. All 16 participants represented average Muscovites with some level of awareness about political news and with a variety of political attitudes.

Related Content

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

While a majority continue to express support for the war and more now sense the military operation has been successful, the Russian public is divided on whether it has led to more positive or negative consequences.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

A slim majority think Moscow should open up negotiations, but it is unclear what they might be willing to concede.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

But those feeling an economic pinch are more likely to say that Moscow should enter peace negotiations.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

Nearly half of Americans (47%) now say Washington should urge Kyiv to settle for peace as soon as possible.