Peruvians Distrust Democracy as Political Crises Deepen

The fallout from the removal of President Pedro Castillo has revealed a young democracy in dire straits.

Last month, Peruvian President Pedro Castillo attempted to dissolve Congress, institute a “government of national emergency,” and form a constitutional convention—triggering his impeachment by Congress and arrest for sedition. In a dizzying series of events, Vice President Dina Boluarte succeeded Castillo, becoming the country’s seventh president in as many years. Ensuing protests over the rocky political transition have since claimed at least 50 lives.

These events have placed Peru’s young democracy under unprecedented strain. Polling from Ipsos-El Comercio, the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (IEP)-La República, and the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) shows that the Peruvian public deeply distrusts nearly every politician and political institution, with only a handful of leaders who challenge corruption earning public confidence.

Corruption and the Roots of Peru’s Political Crisis

Peru has long contended with endemic corruption, but revelations of expansive political bribery by Odebrecht (a Brazilian construction conglomerate) and other firms highlighted the depth of the country’s graft problem in 2016. The ensuing scandal triggered a yearslong political crisis and ensnared three Peruvian presidents, including one who resigned from office; a fourth died by suicide just before his arrest.

Polling from the LAPOP’s 2021 AmericasBarometer suggests that the public is keenly aware of the extent of corruption in the country, which has deeply eroded faith in democracy. Nearly nine in 10 Peruvians (88%) agree that there is widespread corruption in the country—a widely shared belief across age, educational, and socioeconomic groups. In turn, more than half believe that high corruption justifies a military coup (52%). Peru is hardly the only country in its neighborhood to struggle with high-profile political corruption; the Odebrecht scandal also reached the highest levels of government in Brazil and Ecuador. But compared to other Latin American publics, Peruvians are more likely to approve of a military coup as a solution to the problem.

A Failed Reformer

Against this backdrop, Pedro Castillo came into office in 2021 pledging a “country without corruption.” But his 16 months in office were tumultuous, marked by three impeachment attempts, accusations of misconduct, and ideological battles between “soft” and hardline leftists. His government saw more than 50 cabinet changes, five prime ministers, and Castillo’s exit from the Free Peru Party amid a schism with the party’s hardline leader.

More importantly, corruption scandals around kickbacks and financing irregularities sullied his reputation. By October, polling by the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (IEP) showed that five in 10 Peruvians (52%) believed that Castillo was involved in acts of corruption, compared to three in 10 who thought he was not (29%) and two in 10 who did not know (19%).

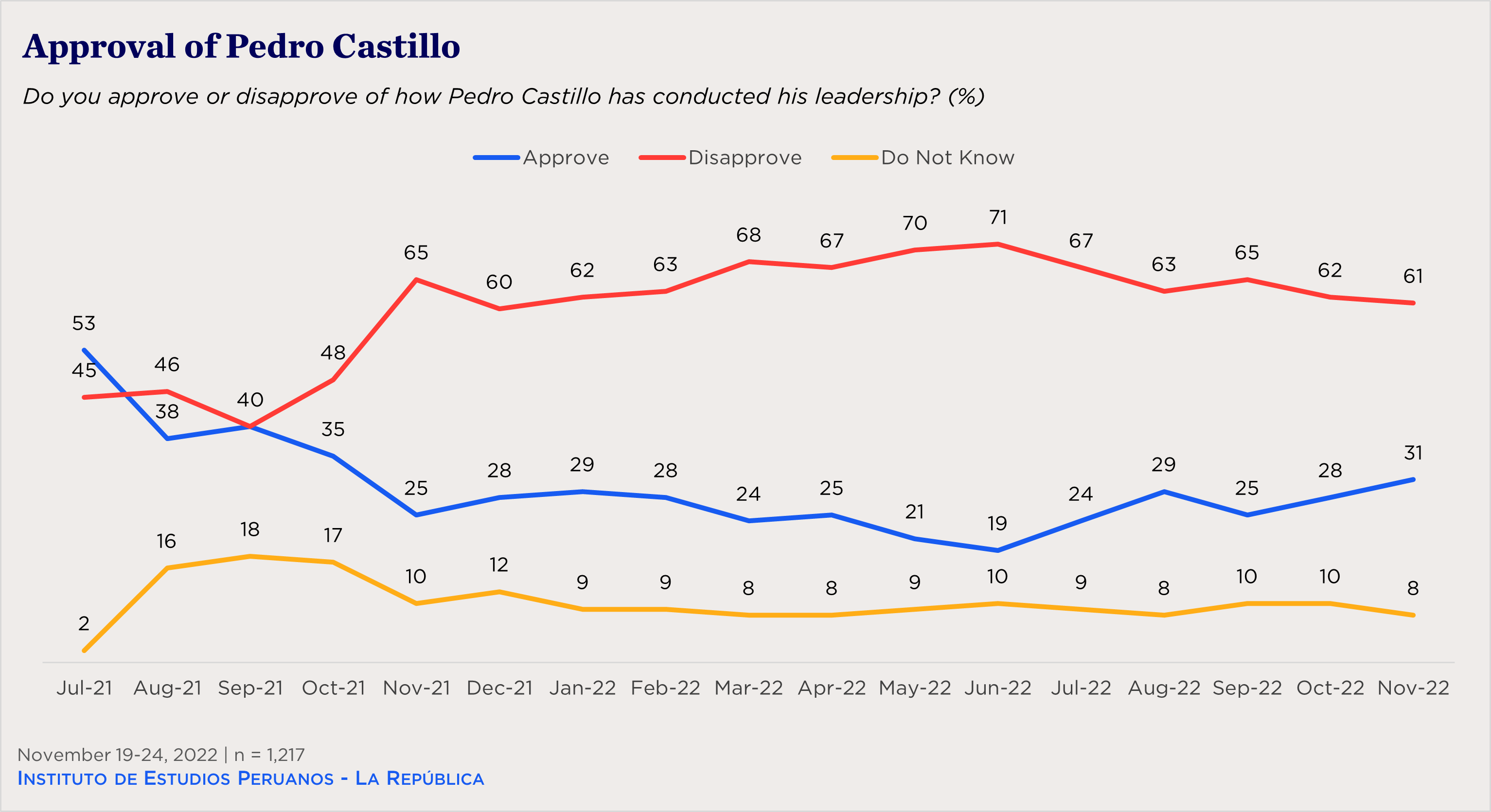

Perceptions of corruption helped to turn much of the country against him. A majority of Peruvians approved of Castillo’s performance when he entered office (53%), but after sensational corruption probes in the fall, only three in 10 supported him from November 2021 onward. Crucially, Castillo lost support across all demographics. While he had once campaigned on class and regional lines, winning the votes of interior, rural, and Indigenous communities, Peruvians of every region (macrozona), socioeconomic classification, age, gender, and ideology came to disapprove of Castillo’s performance. This left him with little political capital to expend as his conflicts with Congress intensified.

No Vindication for Congress

While corruption scandals are the backdrop to Peru’s extended political crisis, these battles with Congress were the immediate trigger for Castillo’s removal. Peru’s executive and legislature are locked in conflict. Fujimoristas, supporters of former dictator Alberto Fujimori and his daughter Keiko’s three failed presidential bids, are reviled by many for their corruption and autocratic aspirations. But in a nation of shifting political alliances, Fujimorism is one of its most stable coalitions—and the movement’s powerful political machinery has brought electoral success in Congress, placing it in fierce opposition to presidents of all political stripes.

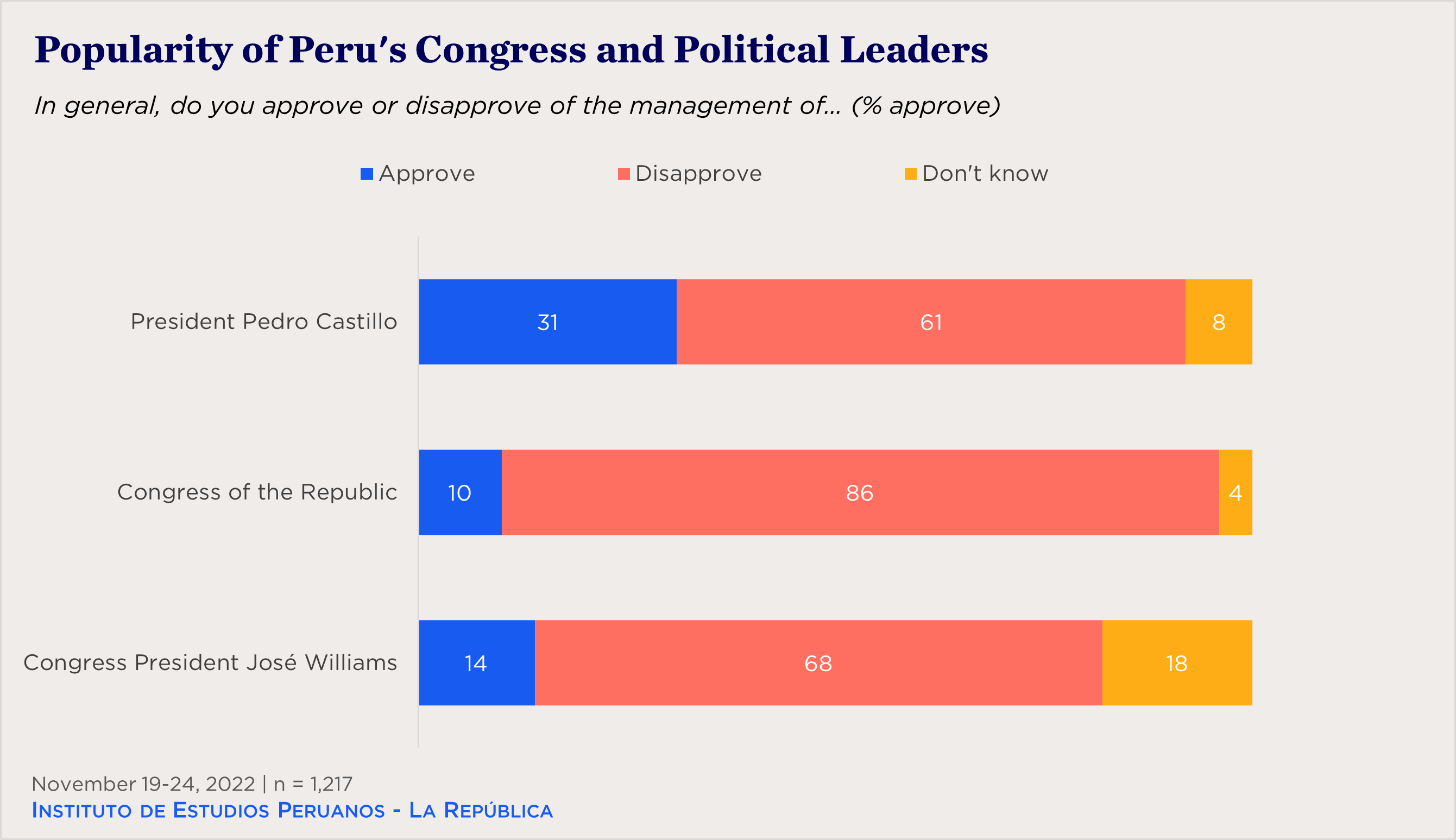

Along the way, the Fujimorista-dominated Congress has arguably become the country’s least popular institution. IEP data show that nearly nine in 10 Peruvians (86%) disapprove of their Congress, which has not enjoyed a net-positive rating among the Peruvian public since 2016.

In fact, Castillo’s battles with Congress could have been a political opportunity. Despite Castillo’s unpopularity, the public has been even more skeptical of Congress’ efforts to obstruct him. Nearly six in 10 (56%) disapproved of the Congress’ decision to prevent Castillo from going to international meetings, while half (50%) opposed Congress’ efforts to denounce him for treason, the charge in its impeachment inquiry against him.

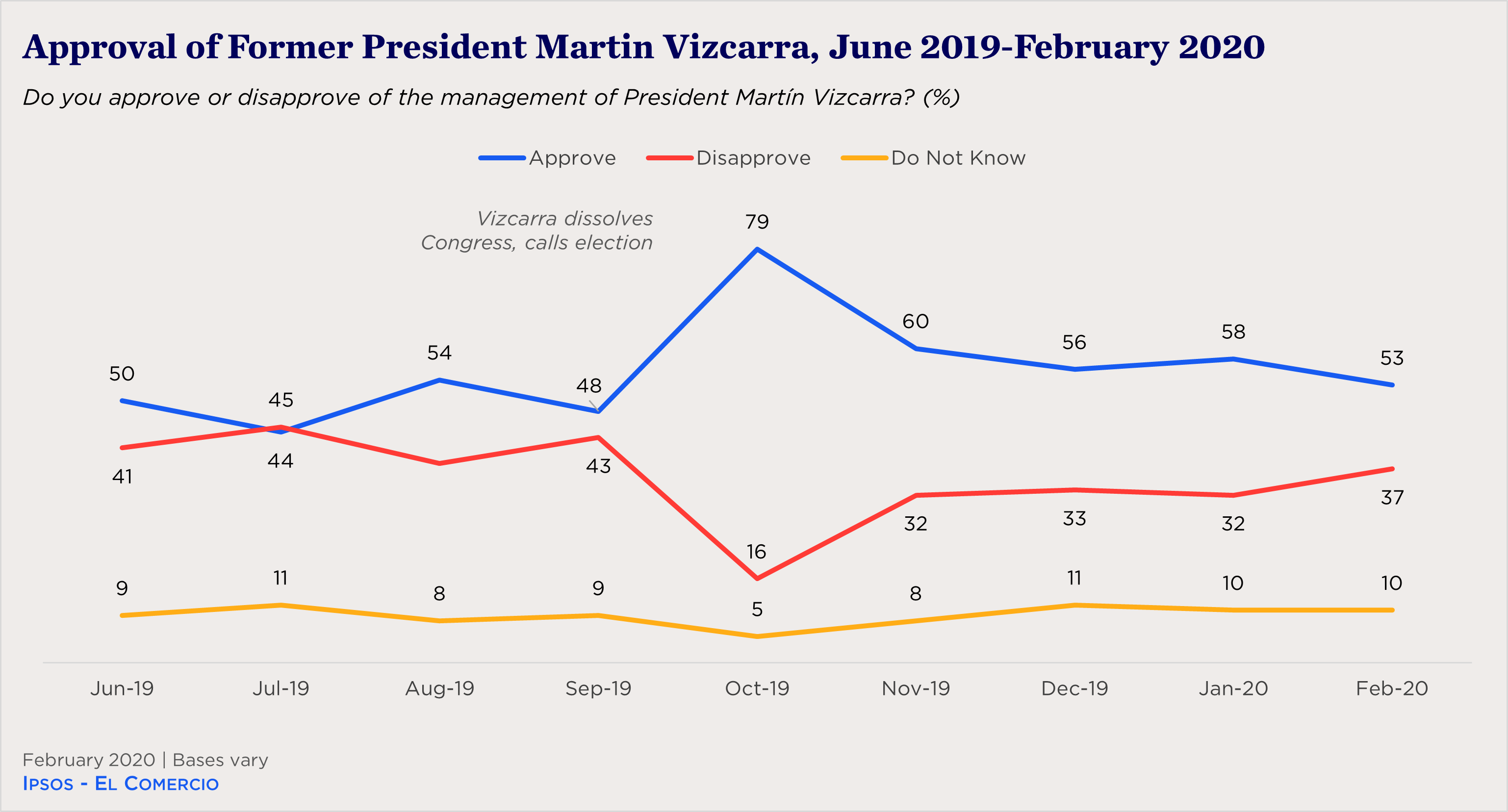

Indeed, the public has often sided with presidents’ attempts to reassert their authority in the past. For example, when faced with impeachment attempts and obstruction from Congress, then-President Martin Vizcarra also attempted to dissolve Congress in October 2019. According to Ipsos-El Comercio polling, 85 percent of Peruvians supported his move, and his successful challenge to Congress led to an enormous bump in his support.

Castillo may have thought he could repeat Vizcarra’s political gambit. But there was a critical difference between the two: their reason for dissolving Congress. Vizcarra dissolved Congress in order to call a special election. Castillo intended to install a “government of exceptional emergency” that would allow him to rule by decree—prompting memories not of Vizcarra, but of Alberto Fujimori’s autogolpe (auto-coup) in 1992.

For the nation’s political class, and perhaps many of its people, that shifted the perception of Castillo’s actions from an attempt to reshape Peru’s ailing democracy to an effort to end it—and marked the swift conclusion of Castillo’s presidency.

With Institutions Mistrusted, No Clear End to Crisis

With nearly every political institution mistrusted, from the presidency to Congress to the judiciary, recently inaugurated President Dina Boluarte faces a monumental challenge to restore faith in democracy. She will need to combat endemic corruption to win Peruvians’ support: among Peru’s recent presidents, only anti-corruption reformer Vizcarra and caretaker Francisco Sagasti ended their terms with positive approval ratings. More immediately, amid widespread protests by Castillo’s supporters, Boluarte is under pressure to defend her government’s legitimacy. It does not help that she acceded to the office by the actions of Congress, the country’s least trusted institution.

History points to a worrying precedent. LAPOP data shows that Peru is one of only four countries in the region where a majority does not express support for democracy in the abstract (along with Haiti, Honduras, and Paraguay). At the same time that democratic institutions are failing, inflation has triggered deep economic stress: a November Ipsos-El Comercio poll showed that 84 percent of Peruvians felt that their cost of living had increased substantially.

Thirty years ago, Alberto Fujimori tapped into Peruvians’ distrust of institutions, skyrocketing inflation, and an economic crisis to institute personal rule. Peru’s young democracy may have just survived a close call. But it is unlikely to be the last.

Related Content

Global Politics

Global Politics

Can Peru’s democracy satisfy protester demands, or will it head into political chaos?

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

President Jair Bolsonaro might be leaving office, but the country’s political trust issues are far from resolved.

Global Politics

Global Politics

Do victories for Lula in Brazil and fellow leftist leaders across Latin America represent a new “pink tide” sweeping the continent?