What Is Currency Manipulation, After All?

Alexander Hitch explains the difference between manipulating and managing a currency and examines the advantages for China to engage in manipulation.

Walking back a campaign pledge repeated just weeks ago, President Donald Trump confirmed that he will not label China a currency manipulator. The reversal came just before the due date for the Treasury Department’s international economic and exchange rate report.

This is another startling, if not wholly unexpected, reversal of policy. President Trump is (now) right on the facts. But determining if a country is a currency manipulator is more nuanced than it seems. How is manipulating, as opposed to managing a currency, defined? And what advantage is there for China to engage in manipulation? For that matter, why would the US want to label any country a manipulator?

To start, currencies either float or are managed. Floating a currency means that the value is driven by demand and supply on the foreign exchange market, while managing means some government intervention to push the currency up or down. An extreme version of managing is a fixed exchange rate, in which a country ties the value of its currency to a more stable currency, often the US dollar (USD). Another type of currency management aims for a middle ground in which the currency’s value moves, with the government weighing in as the buyer or seller. This is the case with the Chinese renminbi (RMB).

Parsing prudent management from manipulation is tricky. Central banks and governments control the supply of money, as well as the nominal interest rate, affecting private investors’ lending practices and influencing exchange markets. And while the United States has rules to help sort this out, there is no global agreement on standards of currency management.

For the US Treasury Department, three criteria must each be met for a country to be labeled a currency manipulator:

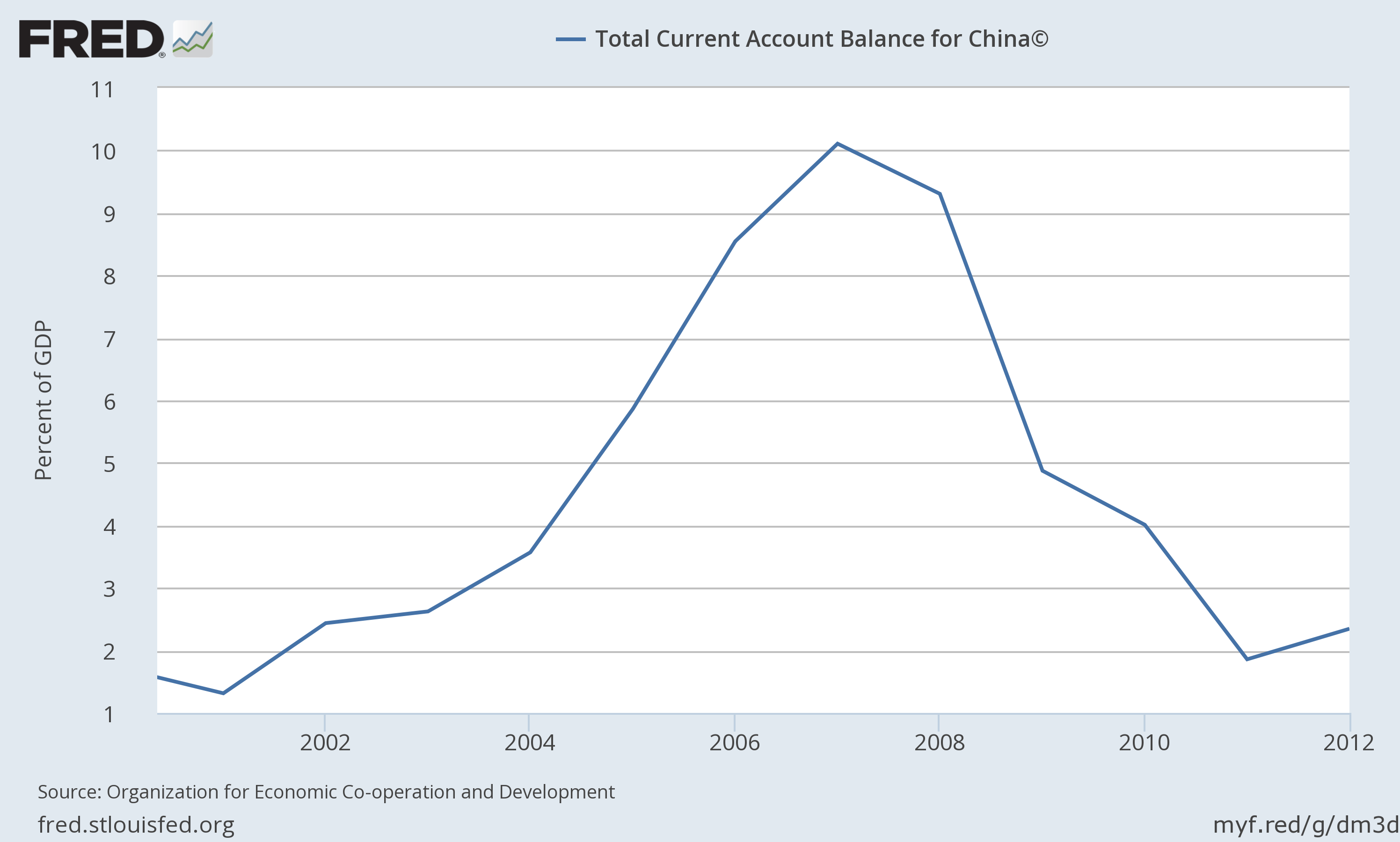

- A global current-account surplus of at least 3% of GDP

- A significant bilateral trade surplus with the US

- One-way intervention in foreign exchange markets of more than 2% of GDP

China only meets the second criterion, with a 2015 bilateral surplus of $336 billion. In earlier years, the global current-account surplus would have also applied.

But what does one-way intervention entail? The mechanics are fairly straightforward.

A country can intervene by buying and selling currencies on foreign exchange markets. If China sells RMB for USD and then accumulates USD as foreign exchange reserves, it depreciates (weakens) the value of the RMB, ceteris paribus, or other things being equal. Likewise, when China sells its foreign exchange reserves of USD to buy RMB, it strengthens the RMB. If the USD’s value falls in relation to the RMB, you would exchange fewer RMB for the same amount in USD. In other words, your USD is worth less.

In the context of an industry—again, ceteris paribus—a "stronger" USD means a producer can manufacture for relatively less in China. With cheaper exports from China, US exports to China look more expensive, potentially relocating or shuttering factories.

Between 1992 and 1994, China was labeled a currency manipulator by the Treasury Department for intervening to weaken the value of the RMB. However, this trend has since abated. The People’s Bank of China has recently been selling its foreign exchange reserves to prop-up the RMB, which otherwise seemed inclined to weaken.

So if China is intervening, isn’t that still manipulation? Perhaps. But China is intervening to strengthen the RMB, which makes US exports more competitive, a hallmark of the administration’s trade-policy agenda.

Suppose President Trump had labeled China a currency manipulator, what would change? Not much. The Treasury Department, which has labeled a country a currency manipulator only four times since the 1980s, would be required to continue ongoing negotiations, albeit with an aggrieved and more intransigent partner. And if China decided to stop intervening, it would likely cause a drop in the RMB, potentially creating an even larger bilateral trade deficit.

This is not to excuse the Chinese economy’s structural concerns. China must address overcapacity in various industries, inflated property prices, and state-owned corporate debt, which all jeopardize economic stability and distort global markets.

But of the concerns, China being a currency manipulator, by the US Treasury Department’s standards, is not one of them.

Although the US-China relationship is complex, there is more to President Trump’s walk back than simply geopolitical chess.