Don't Blame Trade: Low-Skilled Job Losses Will Not Be Solved by Protectionism

President Trump should tackle the problem of job dislocation broadly by building a larger retraining system in sectors where the US possesses a comparative advantage.

The clarion call of the disaffected, low-skilled worker became the soundtrack of the 2016 election. Indeed, President Trump claimed the presidency in no small part by promising to reverse the effects of globalization, railing incessantly against the US’s “horrible” trade deals. It does beg the question, though: Why didn’t anyone consider helping those alienated before?

In fact, they did. The Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program, first implemented in the Trade Act of 1974, is intended to soften job losses stemming from import competition and offshoring. Companies, unions, or workers can petition the Department of Labor for assistance. If their job losses can be tied to foreign competition, former employees are allowed up to three years of benefits to cover living expenses, relocation, and schooling to retrain in an employable field.

Yet TAA has been largely ineffective in combating these trade-related job losses and is in dire need of retooling. Recent data demonstrate that TAA has little effect on placing workers in stronger jobs after retraining; Of the participants that do find immediate employment (74%), median compensation matches only 81% of previous wages, often with fewer benefits.

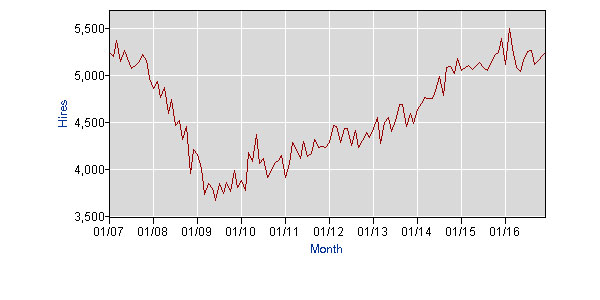

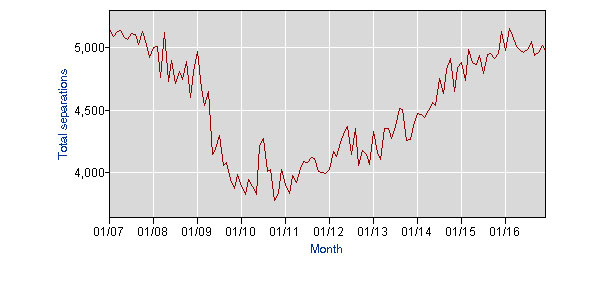

And there’s the question of social equitability. The US economy churns jobs at the rate of approximately 4.5 million separations and additions monthly (see below), with only a fraction due to international competition. Other types of job dislocations – domestic competition, automation – do not receive such generous benefits, even if workers have similar skill levels.

More fundamentally, convincing workers to potentially uproot their lives to wherever they find employment is difficult. For some, proximity to family and friends proves intractable. Likewise, it is hard to convince many older workers of the payoff in returning to school, let alone succeeding.

But the biggest issue is that automation, not trade, has made many jobs in these sectors obsolete, such that any repatriation of manufacturing would likely benefit robots more than American workers.

So, how we can retool TAA to help more displaced American workers prepare for a new type of career? Since education and retraining will continue to be vitally important for work in the new economy, is there a different type of assistance that would be more comprehensive?

We need to roll TAA into a general job-training program for low-skilled labor. This can be accomplished by including it as part of a larger effort to retrain those in low-skilled labor sectors and struggling regions. Ideally, this program would be expanded into a new social contract for all American workers by providing more focused schooling opportunities and supplementing it with tax-free business incentives in particularly hard-hit geographies. To start, eligibility for benefits can be expanded to include industries affected by global economic trends (automation) that cannot directly prove the loss of jobs to trade, per se.

As always, funding is the larger challenge. Currently TAA spends approximately $9,600 per enrollee annually, with an average of 65,000 enrollees from 2013-2015. A new, expanded program of such scope would need funding through a progressive income tax and potentially “pay for success” investments that ramp up as performance benchmarks are met. But at the very least, pairing low-skilled workers with educational programs while also drawing in new business investment in hard-hit communities would create net-positive tax spillovers in future years in regions desperate for investment.

President Trump should tackle the problem of job dislocation broadly—and not focus on trade itself—by building a larger retraining system in sectors where the US possesses a comparative advantage. Yes, determining funding will be key to this effort. But I can think of $21.6 billion ways to begin.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (Hires and Separations in Thousands)